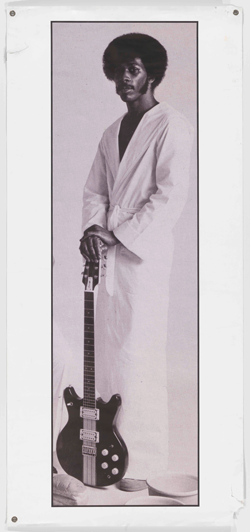

In the early 1970s, years before punk rock exploded in the U.S., three brothers from Detroit started a band called Death. David Hackney and his siblings Bobby and Dannis played blistering rock, a faster version of The Who and MC5. It all sprouted from David’s imagination — he loved rock music, though his family and neighbors didn’t understand why three young black men would want to play it.

Death turned out to be a hard sell. They recorded a demo, but record companies pressured the band to change its name. David refused. After years of rejection, Death split in 1977. Dannis and Bobby relocated to Vermont, starting families and new musical projects. They put their old rock band behind them, telling few friends about their days in Death. Back in Detroit, David struggled with alcoholism and other ailments, and in 2000, he died of lung cancer. Before he passed, he told his brothers to take care of Death’s recordings — the world would want to hear them one day, he said.

David was right. Vinyl diehards had begun to track down Death’s recordings. Then Bobby’s children caught on. What they heard stunned them — they could scarcely believe their dad had played in a band that sounded like punk before punk existed.

The 2013 documentary A Band Called Death tells the band’s story. Indie label Drag City Records reissued Death’s 1970s music in 2009, followed this year by a collection of fresh recordings made by a reborn Death, which includes Dannis and Bobby Hackney and their friend Bobbie Duncan on guitar. Death 2.0 hit the road. Each show, they say, pays tribute to David.

When it opens in 2016, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture will have its own tribute to David Hackney and his group, which decades later has been called not just the first black punk band, but the first punk band, period. The museum acquired several objects from the Hackney brothers, including a mural, a tapestry and Dannis Hackney’s first drum.

Before Death headlined D.C.’s Black Cat in May, Bandwidth joined the band on a tour of the future location of the Smithsonian’s African American history museum. Dannis, Bobby and Bobbie checked out the construction site on Constitution Avenue, then headed over to the National Museum of American History to explore “Through the African American Lens,” a preview of the African American museum’s permanent collection.

Bandwidth’s creative partners the Wilderness Bureau captured the museum tour and Death’s stirring Black Cat show on video; you can see what we saw at the top of this page and on YouTube. But before the members of Death stepped onstage that night, they sat down with us in front of the Woolworth’s lunch counter at the American History museum and opened up about their unexpected legacy.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Bandwidth: What is it like for you to walk through this museum and know that your band’s objects are in here? That you’re a part of history?

Dannis Hackney: I have been humbled. I mean, to see all the things that were done and the courage that these people had to mount up within themselves to do these things — the Tuskeegee Airmen, the Buffalo Soldiers. It makes you feel like you contributed, that our kind contributed. And until you come to a place like this, you don’t realize how much. We owe these people a lot.

Bobby Hackney: Just this exhibit behind me — of the Woolworth’s lunch counter — we owe so much to those four people who sat there. Just seeing this exhibit up close and personal, it just made me cry, as I’m about to do now — because I’m just so thankful for all the pioneers. There’s a saying: You can tell who the pioneers are because they’re the ones with the arrows in their backs.

Bobbie Duncan: For me, this place just lets me know how important education is. You always say if you don’t know where you been, you don’t know where you’re gonna go. To have these things recorded is more important than anything — to bring that to the kids who just didn’t know.

Dannis and Bobby, Death was your brother David’s idea, but he died years before the band found a following. What do you think he would say if he was here today, walking around this museum?

DH: You wouldn’t be able to get David out of here.

BH: Yeah. David loved museums anyway. It would just be incredible for him. I can actually feel his spirit right here with us now, because he predicted so many things about our story — that our music would get known. We’re living another one of David’s prophecies just being right here.

Dannis Hackney’s first drum, now in the Smithsonian’s permanent collection

You talk about that in A Band Called Death, the documentary about your band. In the film you say that David predicted Death’s eventual rise to acclaim. Is that what you mean when you talk about his prophecies?

BH: Oh yeah. That was just one of many prophecies that we’re living now. We have a tendency to call them “David moments.” This right here is a David moment. Because who would have thought that when my mom went into that department store to buy that unassuming garbage can that happened to look like a drum, that that would end up being Dannis’ first drum, you know? [Laughs] And that it would end up here? It’s an honor to her. I’m sure she’s in heaven laughing about this somewhere.

It seems especially remarkable because Death was an inactive band that you hadn’t told anyone about for more than, what, 30 years?

BH: That’s very true, because we went through a lot of rejection. We were an all-black rock band of three blood brothers on the East side of Detroit. Right during the early ’70s, very post-1967 Detroit riot. Most people told us, “Why would you want to play this kind of music? You should be playing James Brown, you should be playing Earth, Wind & Fire or the Isley Brothers.” We loved all of those artists, and we grew up with them, but we just immersed ourselves in rock ‘n’ roll. We wanted to play rock music.

Our production company tried to get record agreements or record labels to be interested in us from around the world, and nobody was interested in our music. They said two things: Our music was too fast, and the name was too scary. In 1970. There’s a million and one bands with names that make that sound tame today. So maybe the ’70s just wasn’t ready for us. And here we are.

“If you asked me if there’s anything in this Death story that I would trade, everything that’s been given to us, I would trade that to spend a day with David.” —Bobby Hackney of Death

But it also seems like when record collectors started finding the Death recordings, the name “Death” was part of the appeal. Maybe if you had had a different name, some people wouldn’t have picked up that record.

BH: Maybe they would have, yeah. They still said that our music was a little too fast. In the days of Detroit, the word “punk” hadn’t even been coined for music. In 1975, if you called me, Dannis or David a punk, those were fighting words. In Detroit, that usually meant one of two things: a black eye or a bloody nose. We were just trying to play hard-driving Detroit rock ‘n’ roll.

But I think due to the rejection and maybe due to the aggressiveness that made our music a little louder, a little faster, maybe that sound was the sound that the historians tuned into when they said that we predated the punk sound by about five years. And we’re grateful for that.

Yeah. You’ve been called protopunk, the first punk band, the first black punk band. But you weren’t trying to make anything like that.

BH: Yeah. We just liked rock music. We wanted to be like The MC5, like The Who, Grand Funk Railroad, Alice Cooper and Mitch Ryder & the Detroit Wheels and all those great bands that we saw in Detroit. We were just into the rock ‘n’ roll. Of course we grew up with Motown and we loved The Beatles, too, like everybody else did, so that’s basically what we were trying to achieve.

So what is it like now being called history makers? Is that surreal?

DH: [Laughing] When we buried that Death music, we never thought anybody was gonna say anything about us being history makers.

BH: That’s right. We never thought it. Timothy [Anne Burnside, from the Smithsonian] said something about a Harriet Tubman piece [in the African American museum’s permanent collection]. And when she was talking about that Harriet Tubman piece, she said this person just had this laying around. That’s almost the way the Death music was. When the world came knocking, there were only two songs, that little obscure 45 we released, and it was like, “Is there any more?” And we were like, “Yeah, sure, we got ’em up in the attic. You wanna hear some more?” [Laughs] And it just ballooned from there. It’s really surreal.

After reviving Death, taking part in the documentary, recording new music and touring, have you reached a point where you feel like you could make up for those hard times? Have you ever felt validated?

DH: It feels like validation, but to try to make up years — I don’t think it’s possible. If we could do that, if Muhammad Ali could take back the years that he wasn’t boxing, or we could take back the years where we was struggling just to buy instruments — you could take back a lot of things. But nothing in history can be taken back. So we just have to forge on with what we have.

BH: It’s a bittersweet burden that we carry. It’s almost like the emotion I felt when I saw this Woolworth’s exhibit right here. I just wish that my brother David could be here. Just like we wish that those people sitting at that counter, if they could just see, to be here. To see the sacrifice that they made, what they did, the difference that they made.

I think that’s the only thing that me and Dannis carry with us. It’s not a thing to be sad about. Because David said, “You guys are going to go on. The world’s going to find out about this music, but I’m not gonna be with you.” We didn’t accept it when he said that, because he was with us. We didn’t want to believe it. And now that we’re living it, I think that’s the only thing that — if you asked me if there’s anything in this Death story that I would trade, everything that’s been given to us, I would trade that to spend a day with David.

Bobbie, what’s it been like in this new version of Death, writing new material?

BD: It’s a blessing, to start with. I had a career of my own, musically. I had my rejections as well, and minor victories and all. [But] David had a way of putting things together. He said, “I’m going to take you somehow from New York and put you near my brothers.” And that’s what’s come along.

BH: That’s one of the things that makes the Death story even more amazing. It was David’s idea for us to migrate to Vermont in the ’70s. And we didn’t know nothing about New England or Vermont, you know? So we find out that according to statistics, in America, we live in the whitest state in the union. Now, how can we find a guy like this [gestures to Bobbie] in the whitest state in the union?

BD: It had something to do with something! Because really. Me? I wound up in New England through the circumstances — I had family up there as well. So I moved up there. Things might take years… but an hour to us is like a snap of the finger to God. I figured that he planned these things for us. He put my family up there, unbeknownst to us, that we would come together. It’s for a reason.

DH: That’s the strange thing about history. Like you said before, we wasn’t trying to make history. We were just trying to make a record that would sell. Those guys sitting at that lunch counter — they weren’t trying to make history, they were just trying to get a takeout order. Or even sit down.

BH: Just have a meal.

DH: History just happens.

Death is currently on tour. Check Drag City’s website for dates.

Pingback: Borderstan Brief | Washington Metro Bugle()

Pingback: Sister From Another Planet » Death Has Been Called The First Punk Band–Now They’re In The Smithsonian.()