Today on WAMU’s Kojo Nnamdi Show, we talked D.C. punk. Or more specifically: why we can’t stop talking about D.C. punk.

The last two years have brought a huge resurgence of interest in the scene’s bygone days, exemplified by the “Pump Me Up” exhibit at the Corcoran last year, Lucian Perkins’ Hard Art DC 1979 book, the fanzine archive at University of Maryland, two recently launched punk-rock archives at George Washington University and D.C. Public Library, the D.C.-themed episode of Dave Grohl’s Sonic Highways HBO series and a whopping five documentaries—one of them still in the works—related to D.C. punk music. (And I admit that Bandwidth has been a gushing faucet of D.C. punk coverage lately, so as the website’s editor, I play a role in this, too.)

But why is all of this reflection happening now?

Today’s Kojo guests—Positive Force co-founder Mark Andersen, Priests singer Katie Alice Greer, the GWU music archive’s Tina Plottel and myself—grappled with that. Andersen rejected that nostalgia alone is driving the deluge. (Because punk isn’t about nostalgia; it’s about the present, he said.) But the activist couldn’t explain why the recent past has been such a fertile period for, well, the past. Cynthia Connolly—the Banned In D.C. co-creator who called into the show—didn’t seem to think this moment bears special significance. She said it seemed like a coincidence, because many of the aforementioned projects took shape years ago and happen to be wrapping up now.

But here’s a theory I neglected to bring up on the air today: In an interview back in July, Punk the Capital filmmaker James Schneider told me that folks should try to preserve the past now because redevelopment is erasing D.C.’s cultural history. “With the city changing so fast, on so many fronts, it’s more important than ever now to ensure that the city’s identity is firmly anchored before a remodeled city takes over,” he said. When these films, archives and other projects began coming together, was it because their creators saw gentrification beginning to erase history? Or is the barrage, like Connolly said, coincidental?

In the hourlong segment, Andersen also made key points about punk rock’s relationship with activism and gentrification’s impact on the very poor (versus the less-urgent effect it’s had on middle-class artists), and we mulled over whether D.C.’s current scene has maintained the sense of social responsibility that’s depicted in the forthcoming documentary Positive Force: More Than A Witness.

Ultimately, today’s show wasn’t all about nostalgia, even though that’s what we set out to discuss. But like many of the ideas revived in these allegedly nostalgic films and archives, we found that talking about the past brought up issues musicians and activists are still wrestling with today.

Listen to the segment over on the Kojo Nnamdi Show website.

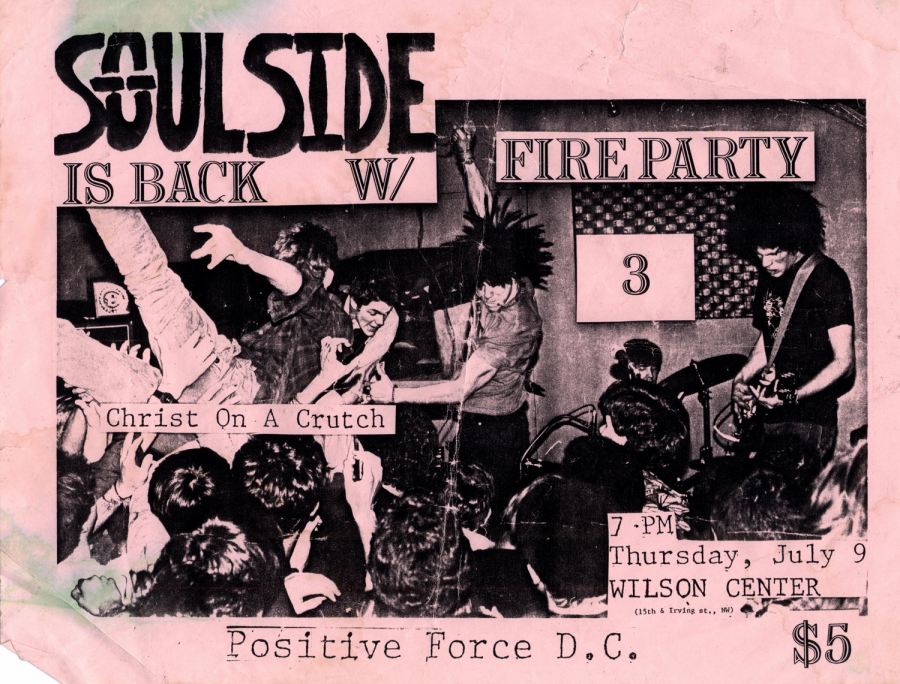

Image by Flickr user rockcreek used under a Creative Commons license.