There’s no missing the Kennedy Center’s “Blue Note at 75” Celebration—the cultural center has devoted a week to programming that commemorates the august jazz label’s 1939 founding. Less conspicuous are the events sponsored by the German Historical Institute and the Goethe-Institut of Washington, who have partnered with the Kennedy Center for the celebration.

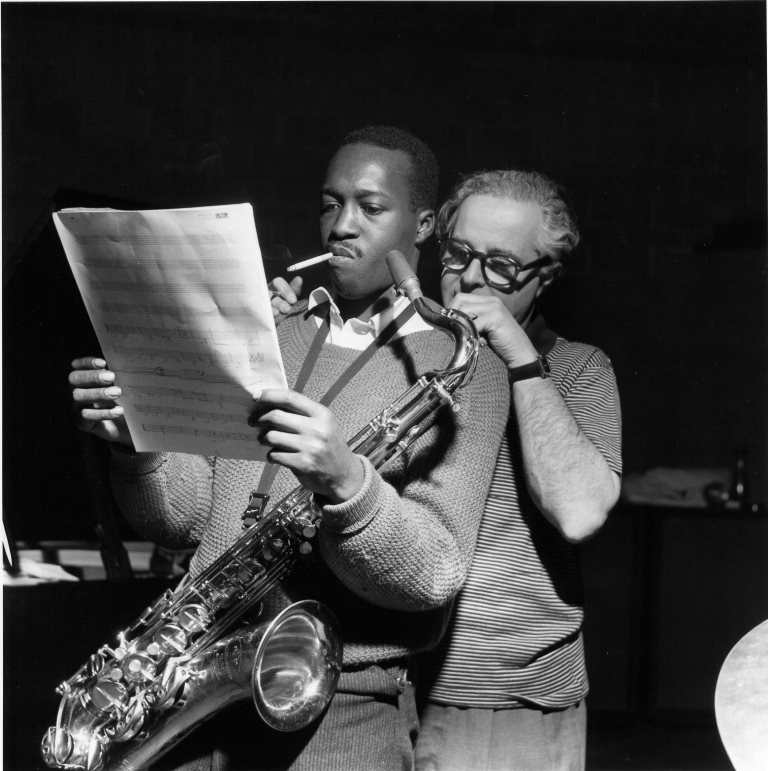

These events—including concerts, films and academic lectures—grew out of GHI’s Immigrant Entrepreneurship project, which in 2012 featured Blue Note Records founder (and German-born immigrant) Alfred Lion. GHI collaborated with the Goethe-Institut to present an exhibition of stirring art photographs from Blue Note recording sessions of the label’s 1940s to ’60s golden age, taken by Lion’s partner and fellow immigrant Francis Wolff, who died in 1971. The exhibition is the centerpiece of both institutes’ Blue Note events.

Michael Cuscuna, a record producer and executive who’s served as Blue Note’s archival gatekeeper since 1975, curates the exhibition along with former Blue Note executive Tom Evered. He spoke to Bandwidth about the importance of Wolff’s photography, as well as that of its subjects in (and out of) the exhibition.

Bandwidth: How did you get involved with the photo exhibit at the Goethe-Institut?

Michael Cuscuna: Well, I own the Francis Wolff photo archive. The Goethe-Institut contacted me about curating a show there, and so Tom Evered and I—Tom used to be general manager of Blue Note—we selected the photos, wrote all the captions and so forth, to really capture a definitive swath of the classic Blue Note era.

Of course, the Francis Wolff photography only captures from the ‘40s to 1967, when Alfred Lion left the label. Then Francis Wolff went from taking photographs to producing records. So it doesn’t obviously cover the whole 75 years of Blue Note, but covers a very important chunk of it.

B: Were you given any particular criteria for photos to use?

MC: Just that they wanted about 30 photographs. So we picked about 40, and let them choose from that. But when we chose the 40, I purposely picked great photographs of more obscure artists. If they had to shave it down, those would be the first to go.

B: Who were the more obscure artists?

MC: Oh, geez. I know [tenor saxophonist] Tina Brooks was one of them. There were a couple of great [guitarist] Kenny Burrell shots, I think I chose one of those. I don’t really remember the others; you know, we did this about a year ago. All the selecting, writing, and scanning was all done last June or July.

B: I don’t know if you counted him as an obscurity, but I was surprised to notice that [pianist] Herbie Nichols made it in.

MC: Yes—that’s one of my more passionate obscurities [laughs]. I think I had to pitch the German Historical Institute that he was really important. And he was. I think one of the great accomplishments of Blue Note was that Alfred Lion loved these idiosyncratic pianist-slash-composers, beginning with Thelonious Monk, and then Herbie Nichols and Andrew Hill. I think the fact that he documented so many and so much of them is why Blue Note’s profile is so large in the history of jazz. So I definitely wanted to have him represented there.

B: And you chose 40 photographs out of how many?

MC: Oh, God, about 2,000? [Laughs] I don’t know—it’s a lot! There’s more than that—2,000 is what we’ve developed from the negatives and scanned. There are maybe 20,000 to 30,000 images, and every three or four years my wife and I just camp out on a weekend and go through them, and find gems that we had never seen before or noticed before. It’s an incredible font of photographic art.

B: How did you whittle it down to such a degree?

MC: Well, the first Blue Note anniversary that I did was the 40th, in 1979. I wrote a history of the label then, and I’ve been writing histories of the label ever since! [Laughs] But at a certain point it’s easy to target the 30 or 40 most glaringly important and influential people in the history of Blue Note, and the impact of Blue Note. So it’s really not hard anymore.

And luckily there are some people—like [guitarist] Grant Green, and [saxophonist] Hank Mobley, and [drummer] Art Blakey—who are just amazingly photogenic.

B: Has there been a public exhibition of Francis’ photographs before?

MC: Yes, there were a couple of gallery shows in New York, at the Morrison Hotel gallery. Before that, at a bookstore—I can’t think of the name of it—but when we put out our first photo book, The Blue Note Photography of Francis Wolff, we had an exhibition at a bookstore then.

The only other public exhibition was for the 70th anniversary; we had it at the Jewish Museum in Berlin. That was quite a moving experience, especially with Francis having barely escaped with his life—and then to be honored back in his hometown at this point was very touching for all of us. But we’re really excited about this one. I hope everyone interested in Blue Note comes to see it.

Images, top to bottom: Art Blakey, 1960; Dexter Gordon, 1962; Herbie Nichols, 1955; John Coltrane, 1957; Hank Mobley and Alfred Lion, 1960. All photos by Francis Wolff/Mosaic Images LLC.