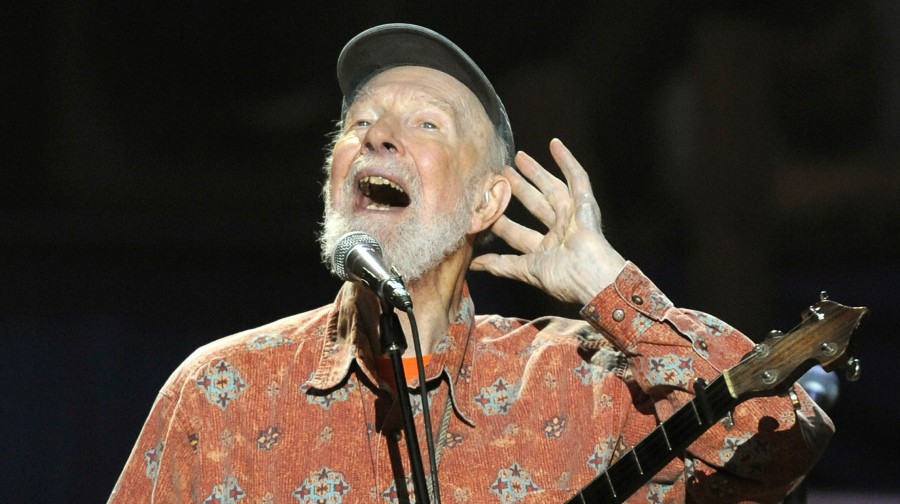

Much will be said and has been said about Pete Seeger, who died Monday at 94, as an activist and musician. Blacklisted, tireless, stubborn, and funny, he wrote a lot of songs that seem to have simply always existed: “Where Have All The Flowers Gone?”, “If I Had A Hammer,” “Turn, Turn, Turn.”

But he was something else, too: He was a person who believed deeply that people should sing, in groups, with harmony, in public — and not just in church. He was a passionate director of probably thousands of pickup choirs, formed at the beginnings of performances and disbanded when they were over. That became even more true as he got older and his voice weakened, but it was true all along.

Seeger’s album Singalong Sanders Theater was recorded in 1980 at Sanders Theater in Cambridge. On it, he plays — and, when necessary, teaches the crowd — “L’Internationale” and “If I Had A Hammer,” but also “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” and even “Hole In The Bucket.” (He was not kidding about things you would think of as camp songs. Ever.) He explains how “Acres Of Clams,” a song about digging for clams in Puget Sound, originated as the 19th-century song “Old Rosin The Beau,” a flat-out old-time pun, and how it went through several variations as, among other things, a campaign song. He teaches them a version of “Old Time Religion” that rhymes “Aphrodite” with “see-through nightie” and uses the expression “I’m a Zarathustra booster.” He sings “Down-a-Down,” a song that spends several verses building up to a punch line about a failed hookup attempt, and he tells them the story of the Homestead Strike.

And always, always, on this record and others, he’s yelling for the tenors and trying to give them their note. These shows were attended by a lot of people who liked to sing and liked to sing in harmony, so they had a built-in advantage. And you can get guys to jump in on a low part. And you can usually get women to sing the melody and an improvised alto part. But oh, tenors. You have to encourage tenors.

But most enchantingly, he leads a “long meter” version of “Amazing Grace.” He explains that long meter means, “No matter how slow I go, don’t stop singin’. Just take a new breath and keep on goin’, and nobody’ll know the difference.”

(Just take a new breath and keep on goin’, and nobody’ll know the difference. Pete Seeger’s Guide To Life, through singing, Part One.)

He takes them through the first verse, the one they all know — “Where’s the tenoooooors?” he sings at one point — pausing on every chord to let it settle and to underscore any note that might be missing. They’re following him, and they’re following each other, and they’re still learning how to make an “s” sound, as a group, with any sort of coordination.

And then he calls out, line-by-line, the verse fewer of them know. “Shall I be wafted to the sky,” he shouts, and they sing it back to him. They’re getting stronger by then. They’re sounding more and more like a choir. It’s lovely. They finish the verse, and they go back to the beginning.

“Amazing grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me. I once was lost, but now –”

And it is here, on “now,” the third time through the melody, that suddenly, abruptly, spine-tinglingly, they are perfect. And he knows, because he held them on the first “now” for about five seconds, but he holds them on this one for 10. They are all suspended, surrounded, momentarily flawless musicians.

Pete Seeger understood something fundamental about humans and music, which is that many people can’t sing on key, but all crowds can. Even without rehearsal, public choirs can be stunning to listen to and thrilling to be part of. And he believed that everyone should do it, that people should retain the ability to get in a room and sing, because it was good for you, and because it taught people to pitch in and be brave.

There’s an old Weavers record where he’s leading a singalong of “Michael Row The Boat Ashore,” and — after making sure the tenors know their part — he says this: “Don’t let your neighbor look at you peculiarly if you sing too loud. You kick ’em in the ribs and get ’em singin’, too.”

(Don’t let your neighbor look at you peculiarly if you sing too loud. Pete Seeger’s Guide To Life, Through Singing, Part Two.)

There are a million Seeger records floating around out there, originals and compilations, and lots of Weavers stuff, too. (Beware the early Weavers releases from Decca, though, because they include the hilarious “Goodnight, Irene” that starts with that goofy violin and which I think either Seeger or Lee Hays referred to in the documentary The Weavers: Wasn’t That A Time as a presentation of the group as “a Barbie doll and three stiffs.” It might not have been “stiffs,” and I can’t locate the movie anywhere to double-check, but it was something equally withering.)

But for me, you want to go for the live records — that Singalong, or his Carnegie Hall concert that includes him singing other people’s songs like “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” and “My Ramblin’ Boy.” There are live Weavers recordings as well, and they’re equally wonderful.

Seeger was an activist for many, many causes, including many that he would undoubtedly have listed above public singing in terms of urgency. Still, his impassioned belief that people should sing, loudly, in front of each other, with throats open and heads back? That’s a big part of what I learned, and one of the many debts I owe him.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))