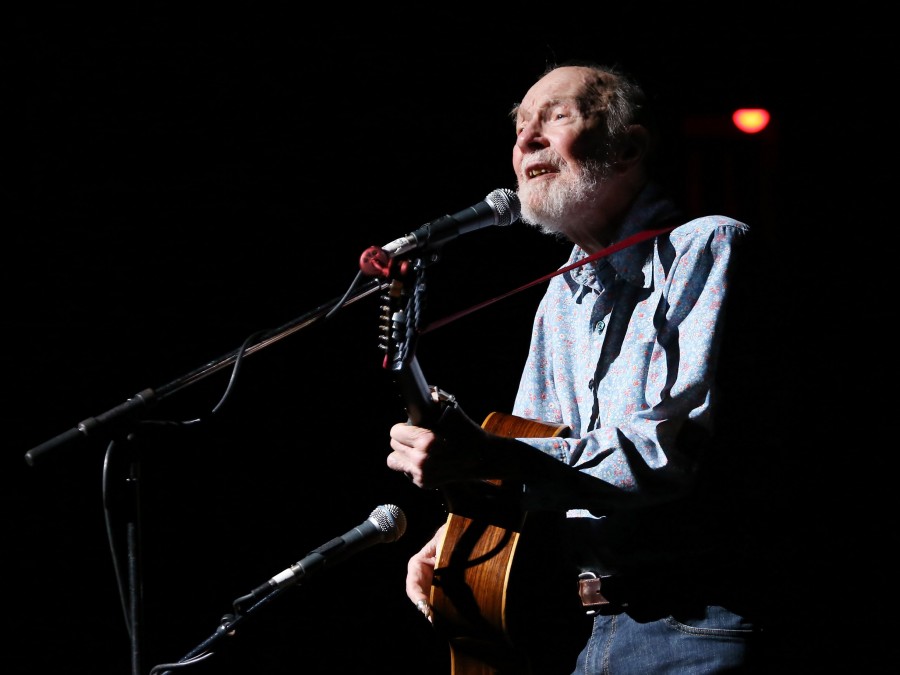

A tireless campaigner for his own vision of a utopia marked by peace and togetherness, Pete Seeger‘s tools were his songs, his voice, his enthusiasm and his musical instruments. A major advocate for the folk-style five-string banjo and one of the most prominent folk music icons of his generation, Seeger was also a political and environmental activist. He died Monday at age 94. His grandson, Kitama Cahill Jackson, said he died of natural causes.

Pete Seeger came by his beliefs honestly. His father, Charles Seeger, was an ethnomusicologist and a pioneering folkorist whose left-wing views got him into trouble at the University of California, Berkeley. Charles Seeger introduced his son to some of the most important musicians of the Depression era — including Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie.

Seeger and Guthrie eventually became fast friends — though they didn’t agree on all things — and crisscrossed the country performing together. Seeger said that as early as 1941, they found themselves blacklisted as communists. Seeger actually was a member of the Communist Party in those early days, though he later said he quit after coming to understand the evils of Josef Stalin.

Following World War II and service entertaining the troops, Seeger teamed up with Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman to form the astonishingly successful folk group The Weavers. Ronnie Gilbert said that from the start, Seeger’s performances were transcendent — whether you were on stage with him or in the audience.

“You got the sense that he was saying and singing way beyond the moment that he was in, the place that he was in. Alone on a stage in front of thousands of people … everybody got it, everybody got his passion for music, his passion for being on the stage, making people sing, having people listen to each other’s music. He was a passionate person, and that was what people saw. People absorbed his passion and his ideals,” Gilbert says.

The Weavers’ version of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene” hit the top of the pop charts in 1950. Other hits followed, including “On Top of Old Smokey,” “So Long (It’s Been Good to Know You)” and “Wimoweh.”

If The Weavers hit an emotional and cultural sweet spot in postwar America, the Red Scare quickly soured it. Seeger refused to answer questions before Congress in 1955 about his political beliefs and associations. He was held in contempt and nearly served a jail sentence before charges were finally dropped in 1962 on a technicality.

But his troubles with Congress finished The Weavers as a major touring and recording group, so Seeger went out on his own again. Shut out of the big gigs, he played coffeehouses, union halls and college campuses to support his family. His wife, Toshi, managed his affairs and raised their children in the cabin they had built in Beacon, N.Y.

He co-founded and wrote for Sing Out, one of the first and most important magazines to grow out of the folk revival. He produced children’s songs and books. But his commitment to political and social causes never waned. Seeger sang and marched nationwide for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. As he told NPR in 1971, “Sometimes I think [about] that old saying,’The pen is mightier than the sword.’ Well, my one hope is the guitar is gonna be mightier than the bomb.”

In 1968 he went local, but, of course, in a big way. Upset at the filth clogging the Hudson River near his home, he spearheaded the building of the Sloop Clearwater, which volunteers sailed up and down the Hudson. Politicians and polluters had to take notice. Seeger, not surprisingly, saw a larger purpose: “Bringing these people together, all these people, is the essential thing, and this is what the Clearwater almost miraculously has started to do on the Hudson,” he said.

For all of his social activism, Seeger said more than once that if he had done nothing more than write his slim book How to Play the 5-String Banjo, his life’s work would have been complete. Seeger’s grandson Tao Rodriguez Seeger plays banjo and performed with his grandfather. He says the paperback, which is chock-full of chords and techniques, is a challenge.

“It’s not a thick book but it’s thick stuff. He doesn’t really explain it too well. It’s sort of quick, it’s got a little diagram, ‘Here’s how you do it.’ But it’s great. It’s an awesome resource. I have a copy,” Rodriguez Seeger says.

Not just through his books but also through his sheer force of presence, Seeger became a model for younger folk musicians. Singer and songwriter Tom Paxton said he learned invaluable lessons from Seeger about how to reach an audience. “Look ’em in the eye. Make a gesture of inclusion, which he did all the time. And above all, have a chorus,” Paxton says. “So I learned from Pete to have something for them to sing.”

Bringing people together and getting them to sing out may be one of Pete Seeger’s greatest legacies. But when it came to saving the world, Tao Rodriguez Seeger says, his grandfather ultimately seemed to question whether the guitar was mightier than the sword.

“[It] troubled him, troubled him deeply that technology was so advanced but our emotional state was so inadequate to cope, that with a push of a button, in a fit of rage, we could wipe ourselves off the face of the Earth. And he really wanted to fix that and always felt like he failed,” Rodriguez Seeger says.

But if Pete Seeger didn’t save the world, he certainly did change the lives of millions of people by leading them to sing, to take action and to at least consider his dream of what society could be.