The party’s over for Columbia House, the music and movie subscription company that has been called “the Spotify of the ’80s.”

Filmed Entertainment Inc., which owns Columbia House, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on Monday in a Manhattan court after more than two decades of declining revenues, according to a company statement.

Although Columbia House moved exclusively to DVDs in 2010, it could not stay afloat in an industry crowded with streaming services. The company’s annual revenues peaked in 1996 at $1.4 billion, but by 2014, revenues had dwindled to just $17 million.

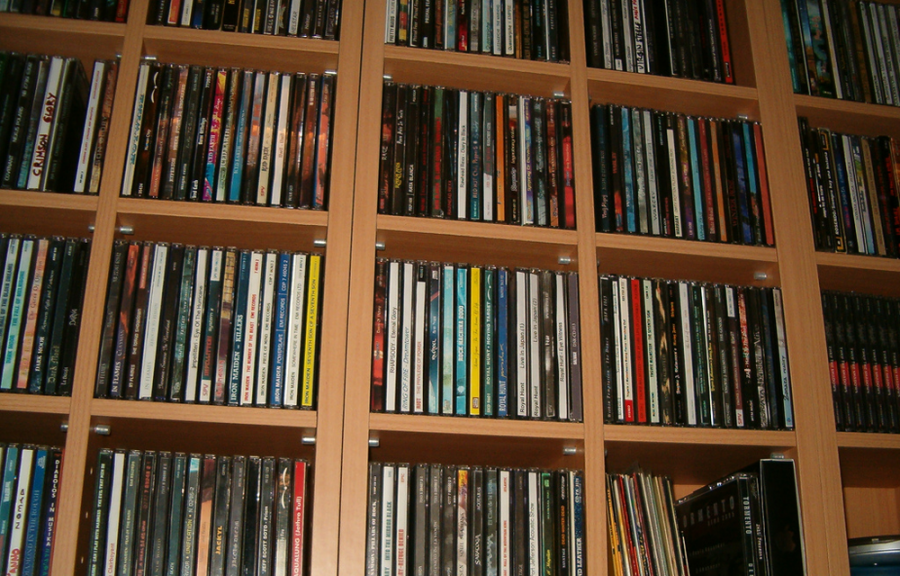

Columbia House “started in 1955 as a way for the record label Columbia to sell vinyl records via mail order,” according to the A.V. Club, which adds that it “continually adapted to and changed with the times, as new formats such as 8-tracks, cassettes, and CDs emerged and influenced how consumers listened to music.”

Columbia House once set the bar for the music-club subscription business model, becoming a household — or at least high school — name through its famous deal: piles of CDs and tapes for a penny.

But with giving away CDs nearly free, how exactly was Columbia House turning a profit?

“The phrase you want is ‘negative option,’ ” Piotr Orlov said, referencing the idea of hooking people with a good deal and then roping them into a contract. (Orlov is a contributing editor for NPR music and former Columbia House director of A&R and marketing between 1996 and 1999.)

“You had a contract that was over a short period of time — two, three or four years — you had to buy a number of titles under regular prices,” he said. “And these regular prices put CD store prices to shame. Like $19.99 [instead of] $11.99. It was an enormous markup.”

Orlov also said Columbia House signed multimillion-dollar contracts with companies such as Sony, Warner Music and others that allowed it to obtain the raw materials and produce its own CDs.

“[Columbia House] was partially owned by major music distributors. [It] would get the music parts — the art and the master tape — and manufacture it themselves.”

Columbia House, however, wasn’t the only one cashing in. Because the CDs came in the mail and customers could pay with cash or check, Orlov said the subscription process lent itself to what he called “low-grade mail fraud.”

“People would fill out a real address with fake names and get 12 free CDs,” he said. “The punch line to this joke is that everybody who worked at Columbia House had done this too [earlier in life]. It really was like an inside joke.”

For another NPR music denizen, Stephen Thompson, Columbia House also represented more than mere music.

“For generations of people, Columbia House was a huge rite of passage — your first foray into maybe wrecking your credit rating, or at least running afoul of an authority beyond your hometown. I was never a member myself, because my parents filled my head with horror stories, but I always look back on Columbia House as, like, Baby’s First Mail Fraud,” he said.

Its business model wasn’t perfect, Orlov said, but Columbia House was valuable in its time.

“What it did do was serve a purpose. If you didn’t have a record store, this was the closest you got to having a good music selection. It put in front of you the ability to buy CDs and send them to your house even if you lived in [the middle of nowhere].”

The FEI statement said the decline was “driven by the advent of digital media and resulting declines in the recorded music business and the home-entertainment segment of the film business.” While streaming services such as Netflix and Spotify surely cut into Columbia House’s profits, Orlov said the main reason for the company’s downfall is something else entirely.

“No one cares about owning CDs anymore,” he said.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))