In 2009, musician and historian Elijah Wald published an overview of American pop from the 1890s to the 1960s he called How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll. The title was a bomb-throwing feint — as Wald told me in an interview, he knew that title would get much more attention than a drier one such as “American Pop From Sousa to Soul” — and as if on cue, one reviewer after another lined up to wave away its thesis. “[I]s rock dead because of [the Beatles]?” harrumphed the Los Angeles Times. “You don’t need to be a critic to know the answer to that question.”

Only Wald didn’t say that rock was destroyed, but that rock and roll was — and the difference is not merely academic. Rock, in the words of critic Robert Christgau, is “rock and roll made conscious of itself as an art form.” Prior to the June 1967 release of The Beatles‘ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, “rock and roll” meant any and everything formally tied to the mid-fifties explosion led commercially by Elvis Presley — doo-wop, surf music, Motown, the British Invasion, James Brown. “We were influenced by early rock and roll … which was not black,” Daryl Hall of Hall & Oates told Musician magazine in 1982 (cited in a Stephen Thomas Erlewine piece for Cuepoint). “It was integrated music. There was no difference between black and white.” As Jack Hamilton points out in his forthcoming Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imaginary, the term “rock,” by itself, was almost nonexistent before Sgt. Pepper; afterward, it almost exclusively denoted white men with guitars.

It also denoted an equally important marketplace turn: 1966 was the last year that seven-inch singles outsold twelve-inch LPs, and albums remained king through the digital age, when individual-track downloads finally surpassed full-lengths in 2008. Two new books by British rock critics, each keyed to specific years, act as a before-and-after of how “rock and roll” calcifying into “rock” acted in terms of who had access to it as the primary, envelope-pushing musical form of the moment.

1966: The Year the Decade Exploded, by Jon Savage, author of the definitive punk rock history England’s Dreaming, is a heavily researched deep dive into both the year’s U.S.-U.K. pop landscape and their attendant sociopolitical ferment, keyed near-entirely to a nonstop parade of hits and duds, many first encountered via pirate radio, which bubbled up as an alternative to the pop-unfriendly BBC and was largely gone by 1968. Never a Dull Moment: 1971 — The Year That Rock Exploded, by David Hepworth, veteran of numerous British rock mags (most recently, the late, lamented monthly The Word), is a breezier but still expansive overview of the high-water mark of rock’s album-oriented maturity, a year Hepworth calls “the busiest, most creative, most interesting, and longest-resounding year of [the rock] era.”

Both books are structured similarly: twelve chapters apiece, one per month, keyed to specific recordings but moving well beyond them. Hepworth is a looser stylist; occasionally too loose, as when he correctly cites the November 1971 release date of Sly and the Family Stone‘s There’s a Riot Goin’ On, only to say many pages later that it “had just been released” at the time of the riots at New York’s Attica State Prison that September. But he’s also sharp and zingy. When he notes, “The year 1971 was the age of the Marshall stack, of mutually assured tinnitus,” or observes that Yes’s lyrics “had to be celestial poetry because they clearly made no sense on this earth,” his mix of garrulousness and dry wit makes Never a Dull Moment a zip to read.

Savage is a more careful stylist and fact-gatherer; not only is 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded (we’ll refer to it by its subtitle from here on) twice as long as Hepworth’s book, it’s far more densely packed. “Primary sources have been used wherever possible in order to eradicate hindsight and to reconstruct the mood of the time,” Savage notes — a stark contrast to Hepworth, for whom hindsight is very much the point. “If any of my children were to be cast away in the year 1971, they would be lost,” Hepworth writes. “However, they would feel entirely at home with the records that were made that year.” That couldn’t be further from what Savage prizes — the constant sense of present tense surprise captured by his carefully cultivated archival diggings.

One reason The Year the Decade Exploded is so much longer than Never a Dull Moment is that the latter is primarily fascinated by rock culture — record labels’ marketing plans or lack thereof, the U.K. live circuit, the day-to-day life of the artists behind the classic albums on which Hepworth focuses. Savage, on the other hand, casts his historical net wide, focusing on everything from nuclear paranoia (keyed to Birmingham, U.K., rockers The Ugly’s’ obscure “A Quiet Explosion,” the kickoff of the January chapter) to Vietnam (via Sgt. Barry Sadler’s number-one “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” March) to Andy Warhol (The Velvet Underground‘s “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” June). He links soul music — Wilson Pickett‘s atomic “Land of 1,000 Dances,” James Brown, Motown — to the rise of Black Power a lot more doggedly than your typical highlight-reel skim, and does the same for the still deeply underground gay rights movement by focusing on the Tornados’ archly campy “Do You Come Here Often?” — produced by Joe Meek, London’s kitchen-sink answer to Phil Spector and a gay man who committed a murder-suicide in February 1967, taking his landlady with him.

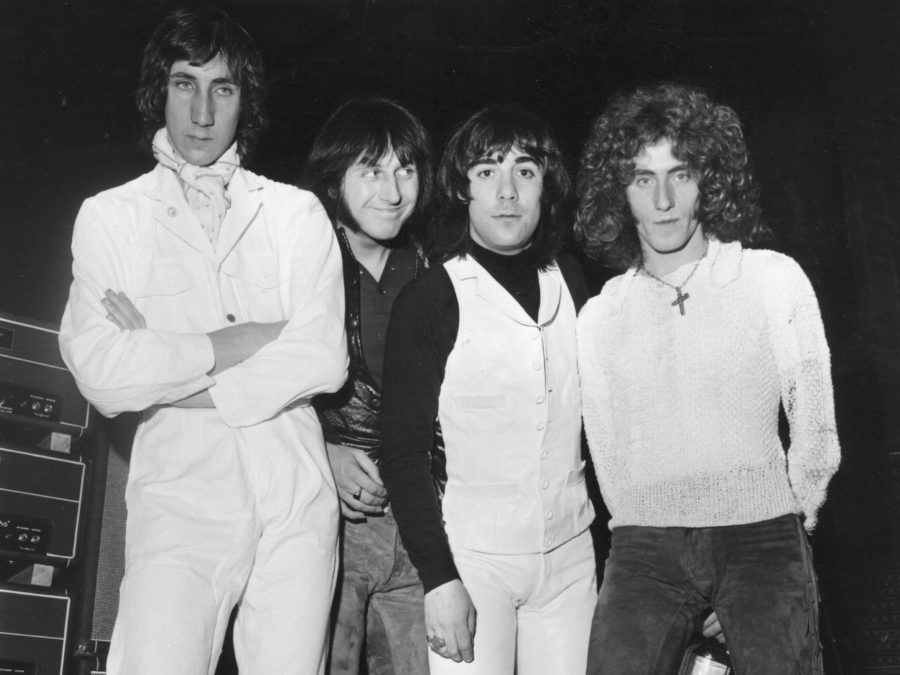

If one of the key tenets of rock is that singles are kids’ stuff while albums where the real meat is, The Year the Decade Exploded wipes away that silly myth repeatedly: Savage’s 45s have as much vaulting, widescreen ambition as the albums Hepworth valorizes. (Being British, Savage uses “pop” rather than “rock and roll,” but the meaning is basically the same.) Take The Who, a band that in very different ways is central to both Savage and Hepworth’s books. In the mid-sixties, The Who were London’s archetypal singles band — by choice, not happenstance. “Before we even approached the idea of making an album that was an expression of our own feelings . . . we believed only in singles,” Pete Townshend wrote in Rolling Stone about the band’s 1971 45s compilation Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy. “In the top ten records and pirate radio. We, I repeat, believed only in singles.”

The February ’66-released “Substitute” remains the band’s masterpiece. “At the start of the instrumental break — which, against type, features only John Entwistle’s bass guitar — [drummer Keith] Moon wallops the hell out of the floor toms in a performance so manic, or drug-deranged, that he had no memory of it after the event,” Savage writes. “I like the blatantness of pop, the speed, the urgency,” the band’s manager Chris Stamp said in a March 1966 quote that Savage cites: “There’s either success or failure — it’s no use bollockin’ about.”

By contrast, Hepworth lauds the band’s 1971 album Who’s Next for being ambitious but not getting carried away. The album’s songs had been intended for an amorphous epic Townshend called “Lifehouse”: “[It] was supposed to be a film, a multimedia epic, a unique collaboration between performer and audience, and, on some level, a ‘crowd-sourced’ piece of art in which the band would facilitate the audience in reaching a new level of consciousness,” Hepworth writes. To him, the secret hero of Who’s Next is associate producer Glyn Johns, who convinced Townshend to abandon the cumbersome, formless “Lifehouse” and instead concentrate on the songs he’d written: “One of the things that made Glyn Johns a production genius was his lack of interest in how things were supposed to work and his readiness to understand how things did work.”

If the kind of runaway ambition of a “Lifehouse” was a path to potential incoherence, though, the type of if-it-ain’t-broke-don’t-fix-it clamping down that led to Who’s Next also lay the groundwork for a wholesale rejection of difference on the part of the largely male, working class rock audience. True, the “heritage rock” industry of Britain (of which Hepworth is part — he helped launch Mojo, the UK’s heritage-rock house organ, in the mid-nineties) isn’t quite the monolith of American classic-rock radio, particularly in the country’s middle, whose flat lands are rendered even flatter thanks to forty ceaseless years of programming the exact same records. But for a Yank, many of the albums Hepworth rightly celebrates — Led Zeppelin IV, The Rolling Stones‘ Sticky Fingers, Jethro Tull‘s Aqualung — can nevertheless be difficult to hear freshly, even aided by a sympathetic reading of his insightful contextualizing. By contrast, the fabulous double-CD 1966 soundtrack Savage compiled for Ace Records never stops surprising, not least due to the sequencing — mostly chronological, but not always. Yes, “Baba O’Riley” is still amazing, but somehow less so on the 1,001st play, especially when roughly 900 of them weren’t voluntary. By contrast, Savage’s inclusion of “Substitute” can still feel revelatory — not least because the song gets extra ballast by Savage leading into it with New Orleans R&B singer Robert Parker’s horn-led party jam “Barefootin’.”

The advantage of the albums central to Hepworth’s book is that they could provide their own context, not to mention that their subjects were hardly shy of vaulting ambition. Led Zeppelin, for example, would have been unimaginable in 1966; it was barely imaginable five years later. “It was customary in 1971 … to release an album as soon as humanly possible,” Hepworth writes. “There was no machine to prime, no marketing scheme to be perfected, no budget to be hammered out, no accompanying image to be developed … no complex hullabaloo to be orchestrated.” Zeppelin didn’t operate that way: Hepworth notes a November 1971 issue of Billboard featured a four-page ad for fellow hard rockers Grand Funk Railroad’s E Pluribus Funk that included “color portraits of all three members of the band,” which compared to the mysterious, band-less cover art of Led Zeppelin IV made Grand Funk appear “gauche and needy.”

The sheer size of the band’s sound was made for arenas and high-end stereos, not transistor radios. When the band was booked to play Madison Square Garden (which it did for the first time on September 19, 1970), Hepworth notes a fellow musician’s double take: “He simply didn’t believe bands could play venues that big.” A festival like Woodstock was one thing; but for the most part, selling out large halls was a rarity in this era, never mind arenas. In the U.K., college halls were the venues of choice (in particular, the University of Leeds, as in the Who’s 1970 Live at Leeds), and as Hepworth points out, drugs were difficult to find and pubs shut down well before the concerts did: “Hence, audiences were overwhelmingly sober.” Merchandise — the full lines of T-shirts, buttons, canvas bags, and other branded gewgaws that now make up so much of the touring musician’s bottom line — basically didn’t yet exist.”

The kind of hard rock Led Zeppelin (and Grand Funk) embodied engendered a hard retreat, both into softer music — such as Carole King‘s Tapestry, 1971’s commercial behemoth and, as Hepworth points out, one of the only big albums of the era selling in large quantities to young women — and the past. One of Hepworth’s key arguments is that in 1971 the marketing of the musical past, in the form of reissues and concerts full of old material, was something “the record business hadn’t yet woken up to,” though that would change in short order. Hepworth’s prime examples are Elvis Presley, already retreating from his 1968 comeback, and The Beach Boys, whose 1971 album Surf’s Up featured a title track that added new overdubs to a Brian Wilson solo-piano performance from 1966; Hepworth calls it “probably the first case of a band making a tribute album to itself.”

Only five years earlier, The Beach Boys had been in rock and roll’s first rank, thanks to the critical (and, in the U.K., commercial) success of Pet Sounds but even more so to “Good Vibrations,” a single that many considered 1966’s most forward thinking. “It was technological yet emotional, sensual and spiritual, with an immediate physical impact and a deeper metaphysical meaning,” Savage writes. But as he also points out, the heady futurism of 1966’s pop incurred its own reactionary streak: Savage’s nostalgia-themed October chapter is keyed to the New Vaudeville Band’s Dixieland throwback “Winchester Cathedral,” which the Grammy Awards naturally named Best Contemporary [R&R] Recording in 1967, beating among others, “Good Vibrations.”

Savage notes that The Beach Boys’ record “spanned both R&B and psychedelia — the biggest new trends of the year.” The Year the Decade Exploded spends lots of time on soul music, particularly its emergence in the U.K., but it could have spent lots more. (Savage notes that he left Jamaican music out nearly entirely for reasons of focus — and, no doubt considering how much research he already did here, sanity.) By contrast, Hepworth doesn’t write enough about R&B because he doesn’t. He does offer a long consideration of Motown, keyed to Marvin Gaye‘s What’s Going On (a good album, not a great one, he says, and I agree), but it feels very surface-level; there’s an uncomfortable component to a line like, “There was nothing Berry [Gordy] did that didn’t have at least some element of social climbing about it,” even though at root it’s basically correct.

What’s more amazing — suspicious, even — is that Hepworth merely grazes some of the most important soul of not only the year but the entire decade. Al Green didn’t release an album in 1971, but “Let’s Stay Together,” issued that November, ahead of the 1972 album of the same title, was a key component of the overall sweetening of R&B then occurring. At the other end of the spectrum, in 1971 James Brown left the indie label King for multinational Polydor, founded the People Records label, and that March lost his band that was anchored by Bootsy Collins and hired another that was led by trombonist Fred Wesley. With the latter unit Brown recorded this third live album at Harlem’s Apollo, Revolution of the Mind, shelving a Bootsy-driven show taped in Paris (eventually issued in 1992 as Love Power Peace). And he churned out no fewer than five R&B top-ten hits. Surely this is worth more than an aside that one of them, “Hot Pants (She Got to Use What She Got to Get What She Wants),” “encapsulates his trademark marriage of carnal and mercantile” — not to mention that both Revolution of the Mind and the Hot Pants album deserve a place on Hepworth’s listing of 1971’s 100 crucial albums far more than, oh, the self-titled debut of soft-rock simpletons America.

And what about Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain, which also makes Hepworth’s 100 album listing but is otherwise absent from the text, one of Never a Dull Moment‘s most curious omissions. (To be fair, both Green and Brown have tracks in Hepworth’s chapter-ending suggested playlists.) Maggot Brain‘s title track has one of the most legendary backstories of 1971 or any other year: George Clinton told guitarist Eddie Hazel to “Play like your mother died,” and Hazel responded with a ten-minute psychedelic blues solo as searing as Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner.” Also, Oedipal psychodrama from a disintegrating counterculture by a bunch of African-American hippie rock and rollers who’d go on to be the most sampled band of all time — how much resonance do you want, anyway? That’s the problem with “rock”: Once seemingly expansive as the sun, with time it’s become clearer how limited a worldview it ultimately is.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))