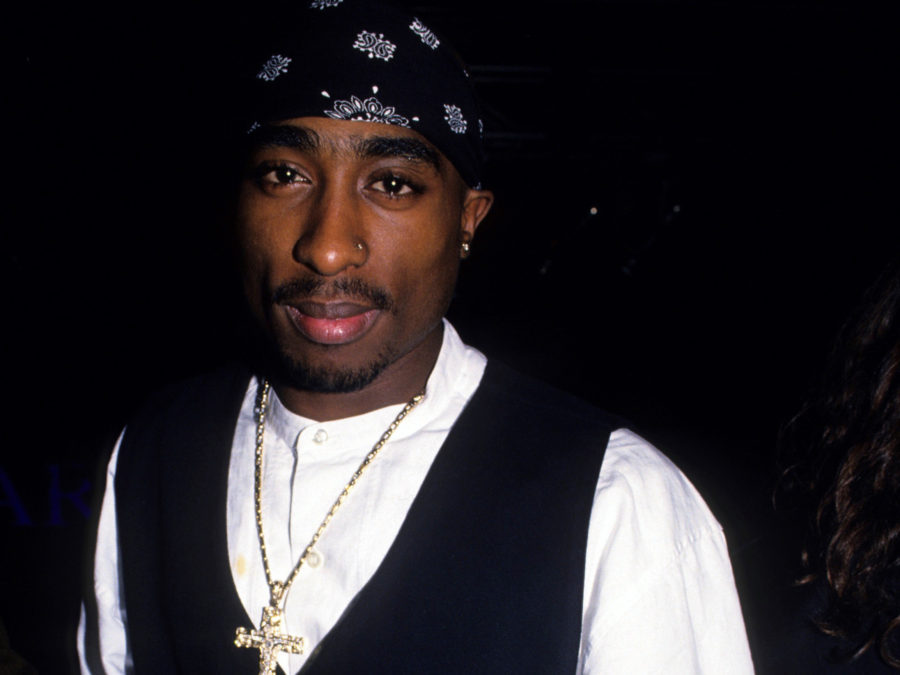

Tupac Shakur was shot four times in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas on Sept. 7, 1996, and died six days later. He was 25. To mark the 20th anniversary of the rapper’s death, poet and author Kwame Alexander has this original commentary. Hear Alexander read the piece at the audio link above.

Tupac Shakur was an enigma — a puzzle many of us could never piece together, but enjoyed trying, a confusing amalgam of profound art and troubled reality. But he was ours. He presented himself like a gift offering: no ribbons, no bows, no paper. He came in a plain box and he came opened — Me Against The World. And I think we embraced him for that, much in the same way we embraced James Dean and Nina Simone and Miles Davis, wild and free and honest — cultural icons with startling contradictions who not only narrated the wonders and the woes of our world; they literally changed it.

We were both born at the inception of rap music, amidst the rampant racism and police brutality of 1970s New York City. Hip-hop was young people’s resistance. It gave us words and beats to better understand the world, ourselves; to turn pain into joy, chaos into community. These were the times that birthed Tupac. And by the early ’90s, when rap music was exploding, he was primed to become its most charismatic and contradictory spokesperson.

His was a short life, with a long, complex legacy left behind. But leaving doesn’t always mean you’re gone. I visit schools every week, and when I ask students to name their favorite rapper, some say Kendrick Lamar, a few say Eminem — but many say Tupac. They quote lyrics from “Letter 2 My Unborn” and “California Love.” They’ve seen Juice and Poetic Justice, his breakout movies, where he seemed to own the camera so brilliantly that it became hard to know where the characters ended and Tupac began. “The unwillingness to let go of Tupac Shakur,” says Kierna Mayo, former editor-in-chief of Ebony magazine, “rests not so much in the tragedy of his sudden death, but in the very significance of his tumultuous life.”

Michael Datcher, a writer in Los Angeles, and I edited an anthology about the life of Tupac. We called it Tough Love, because we were passionate about his brilliance, but clear-eyed in our understanding of where he fell short. “He was in part playing out the cards dealt to him, extending and experimenting with the script he was handed at birth,” writes Michael Eric Dyson. “Some of his most brilliant raps are about those cards and that script — poverty, ghetto life, the narrow choices for black men, the malevolent neglect of a racist society.”

Writing about his problematic relationships with women (Shakur served nine months in prison for sexual assault). Tupac walked a tightrope — between rampage and reflection, between bane and beauty. He was the seventh son, living what W.E.B. Dubois called a double consciousness: one day, nihilistic rampage, the next, compassionate reflection.

Tupac Shakur captivated me, us: his voice, his rebelliousness, his confidence, his poetry. I spent a weekend with him, in 1992 — Charleston, S.C. I fashioned myself a concert promoter; Pac was my first booking. On the way to the venue, my teenage, wannabe-rapper brother, Ade, played his demo tape for Tupac. Way past cool and hyped for the big show, Tupac patiently listened and then extolled the virtues of education over the music business. Stay in school, little brother, he said, with that infectious smile. Be a black genius.

If only Tupac Shakur had lived long enough for us to see more of his.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))