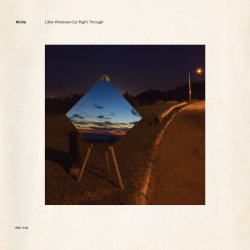

T.J. Lipple’s impact on D.C.’s rock sound can be measured by a extensive list of album credits stretching back more than a decade — including the remastering of several releases from Dischord Records’ vaults — but the engineer/musician has another long-running gig that’s far more personal: He’s a member of acclaimed indie band Aloha, which just released its sixth album, Little Windows Cut Right Through.

Lipple defines his role in Aloha as “musician, producer and buddy of Tony,” or Tony Cavallario, the band’s founder, frontman and lyricist. The “producer” part is probably the easiest to define — Lipple is responsible for shaping the finished sonic product. The rest? He recalls trying to explain it recently to one of his North Springfield, Virginia, neighbors.

Lipple defines his role in Aloha as “musician, producer and buddy of Tony,” or Tony Cavallario, the band’s founder, frontman and lyricist. The “producer” part is probably the easiest to define — Lipple is responsible for shaping the finished sonic product. The rest? He recalls trying to explain it recently to one of his North Springfield, Virginia, neighbors.

“He asked me what I played on the record, and I was like, ‘I don’t know. Sometimes I play nothing, and sometimes I play marimba, and … ‘” Lipple says, trailing off. “I should probably have a better canned answer for that, but I don’t, because it’s true — whenever we make records, my role is ‘guy who makes the record,’ and when I’m mixing it, sometimes it doesn’t need more instruments.”

He says, however, that he’s got carte blanche to record bass, keyboard, percussion and other parts as necessary.

“If something’s not right, I’ll fix it — I don’t care what it is, except for lead vocals. I wouldn’t try to replace vocals, that would just be a mess,” he says.

The results on Little Windows Cut Right Through will be familiar to anyone who has paid attention to Aloha’s career arc: Exquisite but forceful rhythms, polished arrangements and coolly intelligent songwriting dominate the mix, while the band’s original post-punk energy lurks underneath. Synthesizers are definitely more prominent than usual, though. Two Spotify playlists recently posted by Cavallario feature “deep ’80s” acts such as Prefab Sprout and the Blue Nile.

Lipple says Cavallario’s demos for the album took awhile for him to absorb.

“I don’t like the sound of … cheesy ’80s synths. There’s a lot of music with those instruments but, you know, is it good? If you look through my record collection, I just don’t have a lot of ’80s music … I’d never heard of Prefab Sprout and The Blue Nile … until well after we were working on [the record] and Tony played some of it for me. When I heard the Prefab Sprout stuff, it blew my mind — I thought it was amazing.”

One signature of Aloha’s early sound — the use of melodic, mallet-oriented instruments such as marimba and vibraphone — has largely receded. It’s because the original vibraphonist, Eric Holtnow, was a “serious player,” Lipple says, and he doesn’t have the chops to duplicate that kind of playing. Lipple replaced Holtnow in the band in the early 2000s after meeting Cavallario through a mutual friend in Pennsylvania. He moved to D.C. soon afterward, linking up with studio whizzes Chad Clark of the band Beauty Pill and Don Zientara of the famed Inner Ear Studios in Arlington. (Lipple plays with Zientara in The Desperados, a band featuring current and former National Gallery of Art employees.)

The appeal of staying with Aloha, Lipple says, lies in working with drummer Cale Parks, bassist Matthew Gengler and Cavallario, who is a “very nonlinear thinker, but he knows when it’s right.” Parks is one of the rare drummers who is capable of “record-worthy” takes almost instantly after sitting down at the kit, and Gengler plays bass with an understated feel that can be tough to duplicate, Lipple says.

And beyond those relationships, Lipple says it’s tough for him to shake pride of ownership over the band’s sound. A few years ago Aloha considered lightening his load as a studio hand, but didn’t follow through.

“As soon as it got to the point of actually seriously considering giving it up, I just got like a kid with a toy,” he says. “I just wanted it back. Like, ‘This is mine.’ So that’s the last time we considered that.”

As Aloha evolves, and as Lipple’s résumé as a technician expands, he says one thing will remain constant.

“Some people have a way of having the drums just be there without kicking you in the gut, and I don’t know if I could do that,” Lipple says. “I always have to make the drums kick you in the gut, punch you in the face — make it physical.”