Mike Servito has been playing records in public since the mid-’90s, and while the Brooklyn-based DJ is fully capable of plying his trade just about anywhere, he also knows that there’s nothing quite like a queer dance floor. “You definitely turn it up a little bit at a gay party,” he says. “You can be more brash, more vocal, and put a little more feeling and sexuality into it.”

Growing up outside of Detroit, the birthplace of techno, Servito had plenty of peripheral exposure to underground dance music, but it was at Club Heaven, an after-hours spot at Woodward and Seven Mile, where he first witnessed the full power of a gay club environment. “It was queer, it was inner-city, it was black, it was trans. You walk into a place like that, being a kid from the suburbs, and it’s predominantly black and gay and Ken Collier is pumping incredible records,” he remembers. “Just being able to witness that energy was special to me.”

Heaven closed in the early ’90s, and Ken Collier passed away in 1996 (due to complications from diabetes), but he was part of a pioneering generation of queer DJs that ushered dance music through its earliest days. Alongside legendary figures like Larry Levan, Frankie Knuckles and Ron Hardy, he operated during a time when these beats were largely being created, played and, most importantly, danced to by queer people of color. Storied clubs like the Paradise Garage in New York and The Warehouse and The Music Box in Chicago featured undeniably brilliant tunes, but they were moere than just sites for dancing and ushering in influential musical movements — they were places of respite for the queer community. Long before any notions of “safe space” had entered the mainstream, these dance floors also played host to conversations, both verbal and non-, about exactly what it meant to be queer.

In contrast, today’s celebrated dance culture seems almost overwhelmingly straight. Although queer artists continue to lead electronic music’s push into bold new directions, the sounds being created by young contemporary acts like Arca, Lotic, Total Freedom and others tend to eschew traditional dance floor formulas in favor of something more abrasive, experimental, future-facing and conceptual in nature. Compared to what this new generation is coming up with, the sounds of house, techno, and disco have been labeled as downright conservative — and, given their relatively static formulas, the charge certainly carries some weight.

“Those genres are in an era of refinement, not so much innovation,” says Carlos Souffront, a San Francisco-based, Detroit-reared DJ who, like Servito, was also lucky enough to see Ken Collier work his magic at Heaven. From a compositional standpoint, these classic dance floor sounds may no longer seem revolutionary, but they do represent a marked improvement over the ostentatious, Euro-flavored circuit music and Top 40 fodder that has dominated queer nightlife for much of the past two decades. “It was dreadful,” says Souffront, thinking back to his younger days in Detroit. “If I wanted to hang out with gay people, I had to tolerate the worst music that everyone else seemed to love. I always felt like an outsider in queer spaces, but I was desperately drawn to them.”

Honey Dijon, a transgender artist raised on house music in Chicago, shares a similar sentiment while reflecting on her experiences DJing in New York during the late ’90s and much of the ’00s: “I had to make a living as a DJ … so I had to do a lot of compromising and incorporate a lot of [pop] music into my sets. It was really painful for me because I consider pop music to be corporate music …. I respected Madonna and the work she did, and I liked her earlier work, but I felt that if she put out a record, it was something that I had to play in order to appeal to people, especially to gay audiences, [regardless of] whether the record was good or bad.”

Simply put, from the mid-1990s forward, much of queer nightlife suffered from a deficit of taste, something that can be traced back to the devastating impact of AIDS. “A lot of people might have bridged the gap with an oral history of where I came from, but there are not a lot of people left from that generation to hand that down,” says Chris Cruse, who organizes an underground, queer-oriented party called Spotlight in Los Angeles. “There are some, but maybe they weren’t as hedonistic as the people who ended up disappearing in the ’80s and ’90s.” Ron Like Hell, who DJs as one half of Wrecked and works as a buyer at New York’s Academy Records store, remembers the impact that one mentor, a DJ from St. Louis who died in 1992, had on him back in his hometown of Albuquerque. Ironically, he can’t recall the man’s name, but the knowledge passed down remains fresh in his mind. “We had many great long conversations about clubbing and his personal life,” says Ron Like Hell. “He really loved records and clubbing and told me about [Chicago house legend] Larry Heard — no one else did. If he had kept on living, he could definitely be carrying some of that fire into today’s conversation about queer history.”

During the height of the HIV/AIDS era, circuit parties played a central role in queer nightlife, initially as benefits during the worst throes of the crisis. Over time, however, they grew in size and scope, many of them becoming massive “fly in” events dominated by commercial music and what some found to be an alienating aesthetic. “For a lot of us, the imagery on the flyer — the shaved, smooth guy and shirtless, beautiful boys — isn’t really our identity,” says New York’s Ryan Smith, who works as a booking agent and serves as the other half of Wrecked. “We didn’t really feel comfortable on those dance floors. They didn’t feel like home to us, so a lot us were going to see parties in traditionally straight venues.” His DJ partner Ron Like Hell concurs: “60-80% of my club life has been all about preferring to go to more straight parties because of the musical talent [they brought]. These guys were preserving more of our gay disco dance music history than gay DJs were at that time.”

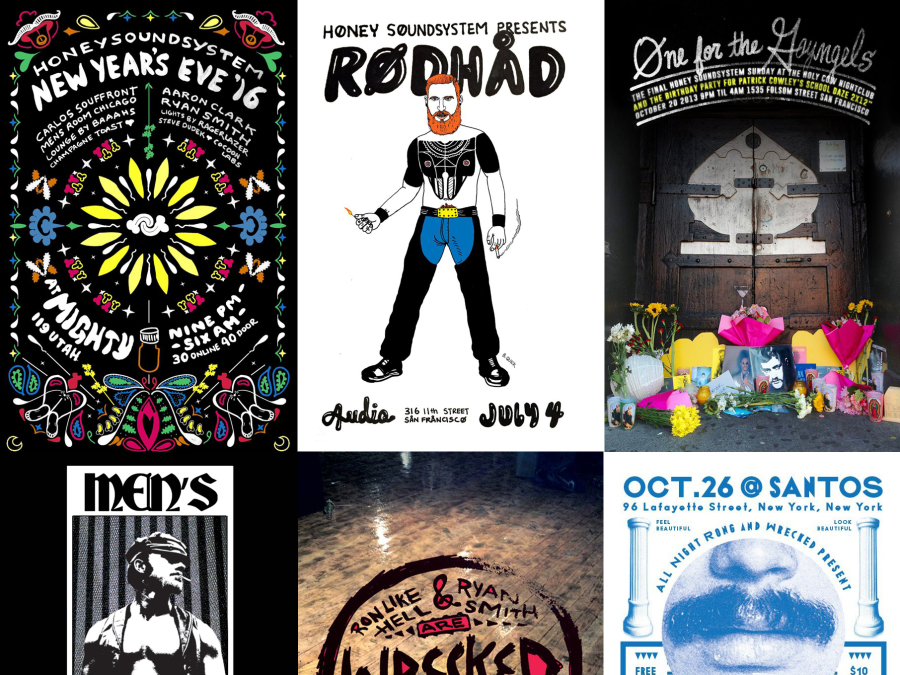

That history is important, and a new crop of queer DJs and promoters are taking steps to reclaim it. Most prominent among them is Honey Soundsystem, a San Francisco collective that simultaneously pushes new sounds while celebrating the legacy of queer dance music. Often explicitly. Through a series of parties and well-received reissues, the crew has been instrumental in spurring the resurgence of interest in synthesizer wizard Patrick Cowley, a brilliant Bay Area songwriter who collaborated with the disco star Sylvester and tragically passed away in 1982, an early victim of AIDS. In 2015, Honey Soundsystem teamed up with Red Bull Music Academy for an event celebrating four decades of queer nightlife at the long-running San Francisco gay club The Endup, and used its DJ residency at Chicago’s Smart Bar as a platform to create a multi-faceted exploration of gay culture called Generators.

And Honey Soundsystem is by no means alone in its efforts. In recent years, a network of like-minded queer and queer-positive parties has developed across the nation, including A Club Called Rhonda and Spotlight in Los Angeles, Wrecked in New York, Dickslap in Seattle, Macho City in Detroit, Honcho in Pittsburgh and Men’s Room, Queen! and Hugo Ball in Chicago, with additional club-nights continuing to pop up all the time. These events are by no means uniform, yet they do seem to share an affinity for tastefully curated programming, transitory environments, uninhibited sexual freedom and a soundtrack of classic (or at least classics-inspired) dance music.

While the music at these parties is in many ways looking backwards — some of the records being played are literally decades old, and even the newer songs on offer are often designed to emulate, or at least reference, the salad days of dance music — they can’t just be written off as exercises in nostalgia. Honey Soundystem co-founder Jacob Sperber cites the intrinsic value of playing a song that’s “written by a gay man, about a gay man,” while Cruse points to the artists that produced these records and the voices that populate them, even in sample form: “A lot of them are black women or black gay men. Those voices are important.”

Of course, queer history and culture goes well beyond music and nightlife, and for much of the past decade the dominant narrative has centered on the drive towards mainstream acceptance. The 2015 legalization of gay marriage stands as this movement’s crowning achievement and queer people are seemingly more visible and accepted than ever before within the context of American culture. Still, not everyone in queer circles is happy with what they see as the increasing normalization of their community. “I have no desire to be accepted or validated by someone who is heteronormative,” says Dijon. “If you look, [straight] relationship models haven’t worked out so well. Their gender issues haven’t worked out so well. They’re still arguing about the differences between men and women.”

“I’m interested in holding on to our culture,” says Cruse. “I don’t aspire to a heteronormative life, so I think it’s important to keep creating these queer spaces, because if you don’t, you’ll see everyone get whitewashed, assimilated — it’s so boring. The desire isn’t for us all to be the same.” His Spotlight parties reflect this sentiment, and not just in terms of the clientele or the impeccably curated music — the environments themselves run counter to the mainstream. Exclusively staging his events in loft and warehouse spaces, off the usual club grid, Cruse puts just as much effort into piecing together the sound system as he does the construction of the darkroom, a key element of every Spotlight party. “They’re there if you want to use them,” he says. “It’s not mandatory. It’s just acknowledging that we have a sexual side to us. If you need to slip off into the darkroom, you can, and come back with a new friend — it’s not frowned upon or embarrassing.”

Chicago’s Men’s Room parties, which require all entrants to remove either their top or their bottoms before they walk through the door, are even more intensely sexual. “We only do our parties in spaces that allow sexuality to take place out in the open,” says resident DJ Harry Cross. Currently held at a venue called The Hole, the party previously took place at the Bijou Theater, the country’s oldest gay adult cinema and sex club before it closed in 2015. Over in Pittsburgh, the monthly Honcho events happen at Hot Mass, a party space inside of a gay bath house. “As gay culture has become more mainstream,” says Honcho founder Aaron Clark, “we needed to have the option for not everything to be family-friendly. It’s probably the only place that people can party in this city, find someone to hook up with, and get a little bit dirty in the club.”

It wasn’t long ago that this kind of overtly sexual attitude was frowned upon in the queer community, at least publicly. Even as new treatments have lessened the level of devastation, the psychological scars of AIDS continue to be felt. “Since the AIDS crisis, the message has been clear: There is only one way to have sex without getting HIV,” says Sperber. “For gay men specifically, as intrinsic as it is to put a wig on, is the fear that sex might kill you. Imagine taking a pill that changes all of that — it is some sci-fi movie s***.” He’s referring to the recent appearance of drugs like PrEP and Truvada, which drastically reduce the risk of transmission and have been credited with helping to reinvigorate the sexual element of queer nightlife. “In many ways, Truvada has created a ‘glory days’ feeling in the clubs,” says Sperber.

“There’s a level of freedom that’s not necessarily present in other parties, a freedom towards hedonism,” says Steve Mizek, a Chicago DJ who heads up the dance-music record labels Argot and Tasteful Nudes, and previously helmed the influential electronic music website Little White Earbuds. “There are a lot fewer inhibitions about body image and really letting go and dancing and doing whatever you want with whomever you want.”

At Los Angeles’ A Club Called Rhonda, a more mixed event which often bills itself as a “pansexual party palace,” being comfortable isn’t necessarily about hooking up — it’s more about being fabulous, with a crowd known for its over-the-top attire and outlandish behavior. “You see the queer people up on stage,” says co-founder Gregory Alexander, “in various forms of dress, with fans, dancing, voguing all over the floor, then you’re going to want to be part of that, because you realize that’s welcomed and put on a pedestal at our club.”

Rhonda’s elaborate decorations are another essential ingredient, as Alexander explains: “We like to go the extra mile and not only make an environment that feels free and interesting, but looks free and interesting.” Sperber takes a similar approach at Honey Soundsystem, stating, “It’s the last thing that certain promoters think about, but for a gay man, it’s just kind of instinctual to want to create a more pleasurable space.”

“It goes back to the stage, the theater,” says Ron Like Hell. “Lights, makeup, wigs, costumes — people love a show. Artists have always been uninhibited, whether they’re homosexual or not, and queer culture goes back to the days of classic, true, amazing entertainment — the spectacle of people being more than themselves, and unashamedly so.” There’s a political element too, as Sperber points out. “The culture of drag and the culture of parades,” he says, “and the idea that liberation came through these things that made people uncomfortable but were actually really theatrical and have been around forever … it intrinsically follows into the party spaces.”

“There’s something in the struggle that creates great art, music and community,” says Nathan Drew Larsen, co-founder of Chicago’s Hugo Ball. A self-described “polysexual, oppositional, surrealist” party with a political bent — its manifesto rails against “carpetbaggers, sanitizers and cultural dilettantes” — Hugo Ball was also conceived to combat the fractured nature of the city’s nightlife. “We just wanted to create something where people could get away from that and mix,” says Larsen. “We’re not a men’s party — I’m transgender …. Our whole point is to be open to just everybody across the spectrum.”

When it comes to inclusion, there’s certainly more work to be done. “Even in the alternative part of the underground, white men still dominate,” adds Larsen. Still, there are reasons to be optimistic. Souffront, Dijon and Servito — all three queer people of color — have seen their profiles rise significantly as of late, both in the U.S. and abroad, where they regularly play at top-line festivals and vaunted nightspots like Berlin’s Panorama Bar. (Last year, Servito was even voted onto Resident Advisor’s annual — and highly influential — DJ poll.) Honey Soundsystem has also seen its gig calendar dramatically spike in recent months. These artists are flying the flag for the queer history of American dance music. “Disco and house music, it’s all derived from the gay community,” says Servito. “A lot of us feel strong about that and more connected to it than ever. The way things are in dance music today, in club culture, it’s predominantly straight. It’s just a matter of time before [queer] people start to latch on and take what’s theirs.”

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))