These days, virtually every type of music imaginable is at our fingertips nearly anytime, anywhere. But for decades, getting that kind of access meant trekking to an actual store, where the store buyers were tastemaking kings. Throughout much of the 1980s, and especially during the CD boom of the ’90s, Tower Records locations across the U.S. were meccas for music fans.

Actor Colin Hanks — Tom’s son — loved Tower so much, he spent seven years making a documentary about the chain. It’s a love letter to Tower Records called All Things Must Pass.

“Tower sort of helped pave the way for your identity,” Hanks says. “For lack of a better phrase, music makes people, sometimes, where you sort of latch on to music as a way of identifying yourself or your tribe. I got that at Tower Records.”

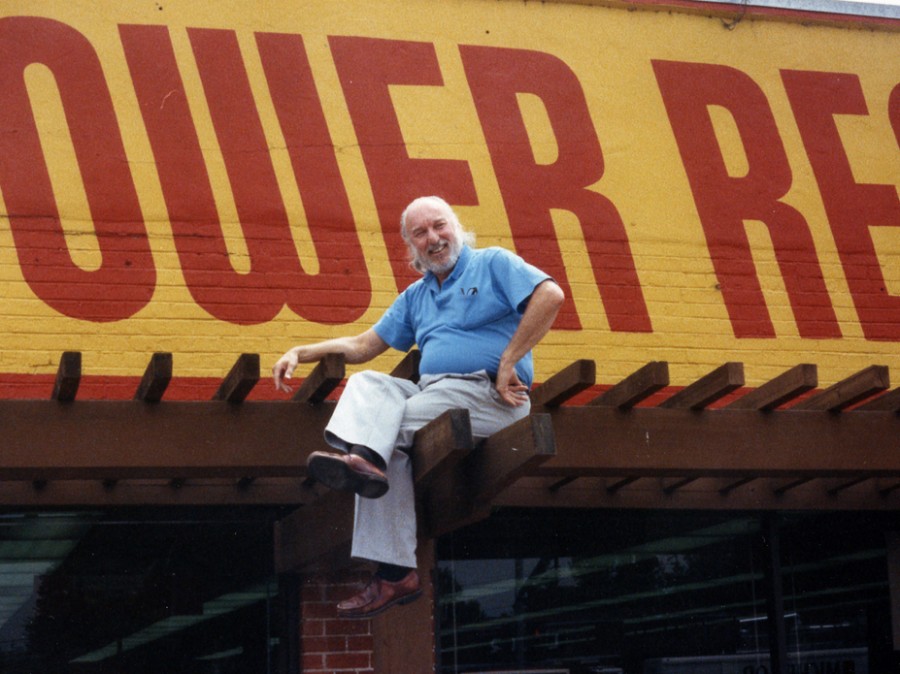

In Hanks’ documentary, you see founder Russ Solomon and his innermost circle — many of whom were there when Tower was founded in California — having a ball building this thing together.

Everyone, from clerks to customers, could feel those good vibrations. During its flush years, Tower was a pilgrimage place for music fanatics — even for the world’s biggest stars. Elton John talked to Hanks about how he’d go into one of the Los Angeles stores every week to buy stacks of new releases.

“Tuesday mornings, I would be at Tower Records,” John says in the film. “And it was a ritual, and it was a ritual I loved. I mean, Tower Records had everything. Those people knew their stuff. They were really on their ball. I mean, they just weren’t employees that happened to work at a music store. They were devotees of music.”

Solomon let them decide what each store stocked, Hanks says.

“New Orleans had a huge heritage music section; Nashville had a gigantic country section,” he says. “Tower was, in essence, a bunch of mom and pop record stores, you know? Although they were all under the same banner, the same name, the same yellow-and-red signage, each one was run individually by the people in the stores: the clerks, the buyers for each individual store, the art department from each individual store. Each store represented its city or its neighborhood in the city. They all had their own style.”

Tower started out as an offshoot of Solomon’s father’s drugstore in Sacramento, Calif. He tells Hanks how he got his friends and relatives to help him get off the ground.

“Luckily, my cousin Ross was a builder — electrical, carpentry,” Solomon says in the documentary. “And so he volunteered, ‘Oh, I’ll go down and fix it up, put some lighting in there, put a new floor in, and paint it.’ And that was it. He went in and did it.”

Solomon’s California inner circle eventually became some of Tower’s top brass, and that family atmosphere spread as the company expanded. Jason Sumney started out as a clerk at Tower’s store at 4th and Broadway in New York before moving into its regional operations.

“Never in my life before, and probably never again, will I experience anything like that,” Sumney says. “Everybody got along, and it was such an amazing vibe. Every day was fun, you know? Even the downs were fun.”

Over the years, Tower grew and grew. It became a multinational empire, with stores and licensees from London to Buenos Aires to Tokyo. But in 2006, Tower declared bankruptcy.

Ed Christman has been reporting on music retailers for Billboard magazine for 26 years. “It took eight or nine years to unfold,” Christman says. “The things that proved to be a mistake, in hindsight, occurred in 1998.”

Christman says that Tower wasn’t alone in the hunger to expand that eventually proved to be its undoing.

“There was at least 10 or 15 large chains that were racing to be the dominant force in music, and Tower decided to take on $110 million in debt,” Christman says. “So they did a bond offering, and they were going to use that debt to drive global expansion. It was just the mood of the day — it was grow and go.”

Tower’s competitors weren’t just other record stores. Big-box outlets like Wal-Mart, Target and Best Buy wanted music fans’ dollars, too. But they discounted CD prices drastically to get customers through their doors, in hopes that they’d also pile things like clothes, pet food, batteries and TVs into their shopping baskets.

“What they did was they looked at the basket — was the basket profitable?” Christman says. “So if there was a lot of other items in there, they didn’t care if it was music or not. Whereas at the record store, Tower Records, they needed everything in the basket to be profitable.”

Tower couldn’t afford to discount CDs much. And Tower couldn’t persuade consumers to spend somewhere between $12 and $19 for an album. Solomon couldn’t persuade the labels to lower their prices or start selling CD singles.

By then, music fans had already started turning to other options, from file-sharing sites like Napster to download stores like iTunes.

Hanks contends that Tower started acting as if it was just too big to fail.

“Tower, in almost 40 years, had always grown,” Hanks says. “It had always made money. It had never lost money. … Well, I think there was a lot of stuff that Tower did not see coming.”

You can hear that in a 1994 promotional video from Russ Solomon, in which Solomon says: “As for the whole concept of beaming something into one’s home, that may come along someday, that’s for sure. But it will come along over a long period of time, and we’ll be able to deal with it and change our focus and change the way we do business. As far as your CD collection — and our CD inventory, for that matter — it’s going to be around for a long, long time, believe me.”

Solomon and Tower had their critics, none of whom are in Hanks’ documentary. In the 1990s, for example, Tower — along with other megachains like HMV and Virgin — was often accused of putting independent mom and pop music retailers out of business. But for Hanks, making this film was a chance to revisit a time and experience that molded him.

“Tower was one of those places. It was special, it was unique,” he says. “You forged a connection with it, whether you knew it or not. I didn’t know it when I was a kid, and it wasn’t until I started making this project that I realized just how informative it was for me when I was growing up. And it’s like that for a lot of people.”

Even though it’s been nearly a decade since Tower closed its doors, its memory still burns bright for fans whose musical tastes were shaped below those yellow-and-red signs.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))