Over the last few years, D.C.’s hardcore punk scene has been memorialized by multiple films and TV shows. But soon, a D.C. native called the “world’s greatest unknown guitarist” by Guitar Player magazine will be the subject of two documentaries that spotlight a twangier side of Washington’s musical heritage.

From the 1960s until his unexpected death in 1994, Danny Gatton’s speedy fingers peeled off rock, blues, jazz and country licks to a small but passionate local audience. He called his music community in Southeast D.C. and Maryland’s Prince George’s County the “Anacostia Delta,” comparing it to the Mississippi region that birthed Delta blues and rock ‘n’ roll.

Anacostia Delta is also the name of Bryan Reichhardt’s forthcoming documentary about Gatton, one of two in the making — and Saturday night, the filmmakers plan to capture a tribute to the fabled musician at the Birchmere in Alexandria, Virginia. Tickets to the event, called “Celebrating Danny Gatton and the Music of the Anacostia Delta,” have already sold out.

“The arc of the film is really around this concert we are having at the Birchmere,” says Reichhardt.

An Indiegogo campaign video for Anacostia Delta:

Gatton stunned the music community in 1994 when he was found dead of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on his Maryland farm. A Washington Post obituary captured reactions from both local and national musicians who “expressed shock about the silencing of a guitarist famous for his mind-boggling chops and blistering speed.” Gatton was 49.

As friends told the Post’s Richard Harrington, Gatton possessed an incredible talent, but he’d never truly capitalized on it. He remained a family man even after — as legend has it — John Fogerty offered him a job playing guitar in Creedence Clearwater Revival. Gatton didn’t like to travel, friends said, and he’d grappled with depression for decades. He preferred to stay near home, in the Anacostia Delta.

Born in 1945, Gatton grew up in D.C.’s Anacostia neighborhood and attended Ballou High School. In 1962 he and his family moved to Oxon Hill in Prince George’s County. A promising musician from a young age, Gatton played local gigs with artists from around town. Guitars weren’t his only passion: He loved old cars just as much.

Gatton had remarkable musical range. He recorded an album called New York Stories with noted jazz players Joshua Redman, Bobby Watson and Roy Hargrove. With his film, Reichhardt seems to want to capture how Gatton — like fellow Prince George’s County resident Roy Buchanan, named a top guitarist by Rolling Stone magazine — played with the greats, but still chose to stay at home.

“People knew [Gatton] here and celebrated guitar players knew him,” Reichhardt says, “but he was not in the popular mainstream.”

Gatton’s scene included the rockabilly, blues, jazz and country musicians who played honky tonks and dive bars across the Eastern Capital region. It’s a culture that Reichhardt has hoped to document for years.

“This is a film I have wanted to make since Danny was alive,” the filmmaker says.

Reichhardt says he’d discussed the idea of a documentary with Gatton before he died, but at the time he was “young and green,” and he didn’t follow through. When Gatton died, he attempted it again but didn’t finish. It wasn’t until he befriended Gatton’s bass player, John Previti — and was urged forward by writer Paul Glenshaw, with whom he’d worked on a 2009 film called Barnstorming — that he revisited the project. Reichhardt calls Previti “the spirit behind the film.”

“John has always wanted to do a film about the entire music scene that Danny came out of,” Reichhardt says. “That’s sort of the genesis of this project.”

Reichhardt fondly remembers his days seeing Gatton play live — and he aims to capture that feeling in his documentary. He and his brother used to see the guitarist regularly at Club Soda, now Atomic Billiards in D.C.’s Cleveland Park neighborhood.

“I would be in awe,” the director says. “Everyone would. It was impossible not to smile at what he was doing. It was just incredible how he would interpret songs… He’d do a funk version of a jazz standard, or a jazz version of a country standard. He was just phenomenal.”

Reichhardt aims to release Anacostia Delta in August 2016, around the same time as another Gatton documentary, The Humbler, is expected to come out. Director Virginia Quesada has been working on the biography film since 1989, five years before Gatton’s death. (Its title references Gatton’s nickname, which he earned for putting so many rival musicians to shame.)

An interview excerpt from The Humbler:

Reichhardt says Anacostia Delta will be more of an appreciation than a straight biography of Gatton. He’ll use footage from Saturday’s Birchmere concert — featuring musicians from Gatton’s universe, brought together by Previti — interspersed with interviews and footage of the guitarist. Bands in which Gatton performed, including The Fat Boys, Redneck Jazz Explosion and Funhouse, are planning to reunite for the show, with appearances from rockabilly guitar man Billy Hancock and octogenarian Frank Shegogue, whom some consider the D.C. region’s first rock ‘n’ roll guitarist.

Reichhardt wants Anacostia Delta to do for Danny Gatton and his community what the film Buena Vista Social Club did for Cuba’s forgotten artists. But there’s one problem: Gatton’s scene doesn’t necessarily have the same allure as the Cubans.

Younger viewers might view the Anacostia Delta scene as a bunch of over-the-hill roots rockers with a penchant for covers, unlike the Cuban artists living amid a U.S. embargo.

The director acknowledges that he has concerns. “I am worried,” Reichhardt says, “and the musicians are worried, too. Many of [Gatton’s] bandmates fear that his music will vanish. The fact that he was as great as he was and that this area as musical as it was will be forgotten.”

But Reichhardt has hope for what his film can accomplish. “Maybe we can create a renaissance for this musical scene,” he says.

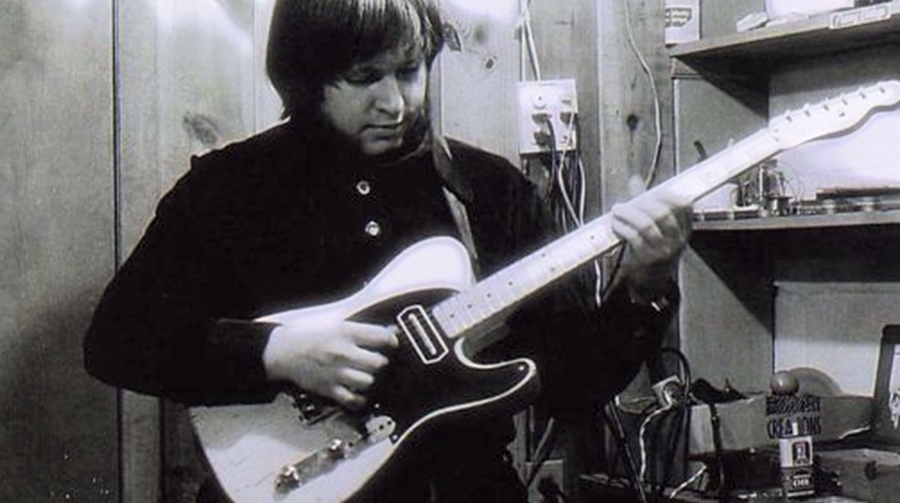

Top photo: Still captured from the Anacostia Delta documentary.

“Celebrating Danny Gatton and the Music of the Anacostia Delta” takes place Sept. 26 at Birchmere. Tickets are sold out.