The music sharing platform imeem thrived from 2004 until its shuttering in 2009 as a safe haven in the wilds of the semi-legal Internet. It was Napster without the piracy, a legal space for music makers and fans to share bedroom composition, videos of their latest dance moves, and the latest streamed — not downloaded — hits. Though many of its 25 million-plus users enjoyed imeem as a way to hear brand new cuts from the likes of Lil Wayne and Katy Perry, others employed it as a dynamic library: a site where historical music could be curated and discussed, and portraits of long-standing subcultures could emerge, document by primary document.

This “willy nilly archive,” as the ethnomusicologist and DJ Wayne Marshall called imeem in a widely circulated 2010 blog post, allowed for far-flung students of music culture — college professors, book authors and documentary filmmakers, and moonlighting amateurs alike — to access rich collections representing dance worlds like Chicago footwork and Memphis jookin, the sound worlds where Trinidadian soca, U.K. dubstep or Southern trap music thrived without making the U.S. airwaves and countless other “nu-whirled publics” whose products wouldn’t end up in the Smithsonian any time soon.

The advent of streaming was a game-changer for someone like Marshall, a connoisseur of older and emerging music surviving beyond mainstream. Material that once could only be found through diligent fieldwork — whether that meant connecting directly with far-flung communities or digging like crazy in record store bins or basement library stacks — was now immediately accessible, and framed by lively exchanges that often included the music-makers themselves. Streaming was changing music scholarship, as well as the day-to-day pleasures of any curious listener who could now instantly pursue a new fascination. The story of pop, as defined through lineage of widely familiar artists and styles (Elvis, Motown, classic rock) was now being expanded and challenged by the quickly accessible greatness of the forgotten and the marginalized (Awesome Tapes from Africa, deep Southern gospel, regional punk). Music history was bursting open, and not just for credentialed historians. Fans falling down rabbit holes could feel like experts after a long lost weekend of listening. Public libraries were digitizing, catching up to the rapid (and often copyright-careless) activities of private collectors. Specialty labels were popping up, turning preservation into a sometimes trendy and even modestly lucrative pursuit. Even as online music shook the present-day music business to its core, the vast past of music was becoming much more audible.

The truth is, most music available on the Web is archival, whether that term refers to Justin Timberlake B-sides or the very first sound recordings.

But that past has proven unstable too, in terms of both access and our ability to fully understand it. Marshall’s blogged celebration of imeem, for example, was a wake. Purchased by MySpace in 2009, it was quickly absorbed into that larger platform, its structure dissolved, access to its streams lost. Its grounding in Flash-based media instead of the perennially controversial (and, because of copyright, often illegal) act of downloading, Marshall noted, was one reason imeem-as-archive was so precarious: The material itself, not simply the playlists and comments that contextualized it, instantly became unavailable. But even when that same stuff resurfaced in other places, like YouTube, it was different. Unlike older archives cataloging material objects, where bibliographies and librarians’ filing systems and even liner notes helped explain and connect sources, informal streaming archives like imeem were, as Marshall said, “tactical” in nature — designed to benefit users in the here and now, not cement meanings for all time. “When platforms go poof, a lot more disappears than awesome dance vids,” Marshall wrote, lamenting the “broader contextual frameworks” no longer visible.

Five years later, Marshall, like most music scholars within and outside the academy, still uses streaming platforms for research. Much of what he found on imeem eventually resurfaced on YouTube — the number one source of music discovery for young people today, and one that educates its habitués about the past as thoroughly as it provides them windows into the present. Spotify serves as a companion tool, its ever-growing roster of albums complementing the sometimes rougher stuff on the video channel. Marshall uses both. He’s grateful for their richness, but remains skeptical about their reliability.

“As a teacher of music history, it has been downright incredible to be able to assemble playlists on YouTube or Spotify, of pretty much anything that’s been recorded,” Marshall wrote in a recent email. “But I don’t take this for granted or imagine that it will always continue like this. On one hand, there is definitely a pressure to monetize and hence to wall off some of this culture from people who can’t pay for it or refuse to surrender their privacy in exchange. If Facebook owned YouTube, I might not be able to use it anymore. On the other hand, there’s a ‘genie out of the bottle’ phenomenon here, and people are assembling their own media archives, off the cloud, which will serve us when we inevitably need to reconstitute them after the next round of corporate failures. Enthusiasts and artists have different motivations than corporations. That gives me hope.”

When most people talk about streaming, they’re thinking about new work by current artists — how Katy Perry’s chart position is affected by Spotify or whether independents artists are getting paid enough for their latest releases. But the truth is, most music available on the Web is archival, whether that term refers to Justin Timberlake B-sides or the very first sound recordings. Have you made an ultimate soft rock playlist? Explored Eurodisco? Decided one day that you really need to learn about the Gershwins? You’re participating in the reimagining of the musical past.

The heady promise of having what seems every sonic yesterday at one’s clicking fingertips is profoundly changing the way music history is being written, and the way fans experience it. Grade schoolers use streaming services to provide the soundtrack for class projects; academics with half a dozen books to their names can track down material that, in earlier times, they could only find in far-flung university collections. Streaming music is an essential classroom tool, all the way to the college level. “If I want to introduce Nina Simone to my students, I have a choice of streaming virtually all of her recorded material and many live performances — indeed, seemingly more each day, as more and more people upload materials,” wrote Gayle Wald, a professor of English and popular music culture at George Washington University. But the bounty, Wald noted, comes with built-in problems. “YouTube, in my experience, has a pretty lousy track record for annotating performances. I feel like YouTube users bat about .500 when it comes to correctly noting the year and source of the videos they post.”

A complex ecosystem is evolving that links the National Jukebox of the Library of Congress with clearly commercial services like Spotify and fan community-compiled sites like redhotjazz.com. Each fills in the gaps of the other. “Official” archives — those within public libraries, museums, or universities — are better organized, but have been slow to digitize. Spotify has complete albums, but no commentary. YouTube seems to have everything, but because anyone can contribute to it, it can’t be trusted as a source. What is a scholar — or a regular enthusiast, trying to learn how certain music styles or cultures really evolved — to do? It’s a far cry from the experience of entering a physical library, where the rules of cataloging and the guiding hands of archivists determine one’s experience.

“Archiving used to be the domain of the tangible,” Cheyenne Hohman, the director of the Free Music Archive, wrote in an email. Hohman holds a degree in library science, and she sees pluses and minuses in the shift to the cloud. “Now that we’re in a sea of born-digital media, storing and accessing information and media has shifted to favor the ubiquity of web-based collections. But would I call an aggregator like Spotify an archive? Not really, because if they go bankrupt, they’ll probably shut down, and they’re not motivated by preservation and access as much as they are interested in providing a commercial music platform for consumers.” Hohman’s concerns echo Marshall’s, and reflect the reality that commercial streaming services aren’t primarily intended for the public good. They exist to make money, whether through subscriptions or ad revenue.

“If Facebook owned YouTube, I might not be able to use it anymore.” –Wayne Marshall

A deft scholar uses them strategically and always double-checks their data. Elijah Wald (no relation to Gayle) has written on subjects ranging from the Delta blues to Chicano rap to Bob Dylan at Newport. He describes his researching process as one of check and balances. Sites organized by fans, many among them serious collectors, allowed him to hear old 78s when he was writing about crooners from the 1920s. A project on X-rated rap required that he spend hours on YouTube, where that stuff exists in a kind of accessible underground. While writing new Dylan book, Wald sprung for a Spotify premium subscription because he wanted to hear 1960s folk albums in their entirety, with songs in their original sequence. He uses academic archives mostly for photographs and books, not music, because little of what he’s needed to hear has been available there. “But that’s changing very fast, and I’m thrilled,” he wrote.

The fact that his readers have the same access he does to all of this source material has challenged Wald as a writer. “Now, when I write a book, I can take it for granted that virtually any interested reader can hear virtually any recording I mention,” he wrote. “That really is a huge difference, and makes my job both easier and more difficult, since it frees me up to assume that interested readers can hear for themselves, but also means I need to hold myself to a higher standard of description because readers can hear for themselves.”

Wald has been an independent scholar for most of his career, and once he would have had to scramble to access key archives contained within universities. The huge boon of official archives is that they’re professionally organized and held to a common standard of documentation and cataloging. But getting into them, in the past, required travel and an affiliation like a university job or a book contract with a major publisher. Now the playing field is more level. At the same time, new uncertainties have arisen about unofficial archives’ reliability or organizational clarity.

Every scholar interviewed for this article regularly uses both official and unofficial archives, leaning more toward the latter because of greater accessibility. Wayne Marshall expressed a common concern, however, when he noted that commercial streaming platforms serve the needs of the market first. Preservation isn’t a money-making prospect, and curation has come to mean little more than opinionated compiling, with no emphasis on historical accuracy or even useful context. And laws like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, while benefiting music makers and distributors, restrict free use.

“Ephemerality is a key problem — and that goes not just for the media objects themselves but all the discourse and metadata and meaning gathered around them,” Marshall wrote in an email. “More problematically, because these sites take it upon themselves to police content and remain in the ‘safe harbor’ of such things as the DMCA, they profoundly shape what ultimately gets archived and what does not.”

This is where the heroes of music preservation intervene, creating new systems that increase accessibility to reliable, well-protected information. Efforts are being made to both preserve digital music culture and digitize historical music — in a massive way, through the Internet Archive, the San Francisco digital library whose stated purpose is to preserve as much of the public Web as possible; and within more select avenues, like the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, a nonprofit organization mandated to preserve all recorded culture, no matter the format. ARSC is doing important work to create dialogue about sound preservation among academics, individual collectors, and commercial entities like record labels. Its granting program, annual conference, and active listserv are helping to bring sound preservation into the digital era by connecting old-fashioned collectors, who are often still firmly dedicated to the “thinginess” of recordings, with archivists and others working on the digital cutting edge.

“ARSC is unique among organizations dedicated to our audio heritage in bringing institutional repositories, private collectors, scholars who work with recorded sound, and commercial industry professionals together at the same table,” wrote sound preservationist and current ARSC President Patrick Feaster. “Too often it seems these groups don’t talk with each other otherwise; in some cases, they’ve even developed unfair and mutually hostile stereotypes about one another. Getting a dialog started across these boundaries isn’t easy, nor is avoiding friction when the conversation encroaches on certain controversial topics, such as what information is essential to provide when describing a given record. But all parties are either passionate about historical recorded sound or indebted to it for a living — often both at once. All parties also contribute in some essential way to keeping that heritage alive. By exposing each ‘group’ to the perspectives and interests of the others, we help foster a shared understanding and expose opportunities for collaboration that might not otherwise be apparent.”

Feaster, who has a PhD. in folklore and ethnomusicology from Indiana Unviersity in Bloomington, is a shining star among sound preservationists. He began his music-loving life as a classic collector, becoming fascinated with Edison wax cylinders and other old forms as a kid in the 1970s, but he’s evolved into an avid digitizer, gaining fame for resurrecting the sounds of the oldest known recordings. He believes that such work is the only means for old sounds to survive. “Many formats are degrading physically over time; equipment needed to play them is becoming scarce, as is expertise in using and repairing the equipment,” he wrote. “If we don’t digitize the content now, someone might still be able to hold the physical carrier in twenty years — but not to listen to it. Sure, there’s a loss there, but it’s an inherent one: part of the nature of the things themselves, like beautiful flowers wilting and dying.”

For him, the work of recontextualizing sound is no different in the digital age than it was when he was sifting through old stacks like the one in Indiana where he found the oldest known recording. “Yes, the sounds are “decontextualized” when you stream them online from a server in California in a way that they weren’t when I played the originals on an Archeophone (not a vintage machine) in Maryland,” he wrote. “But they were also radically decontextualized at that earlier point: In most cases, I didn’t know anything about the circumstances under which the records were made, or the people who had made them. And a month or two later, when I was listening to the sound files at home in Indiana to figure out what they were, I felt that as by far the bigger loss: I cared about not knowing the stories more than I cared about no longer having direct physical access to the cylinders. In some cases, I was able to reconstruct the stories and identify the speakers and performers. At that point, I felt they were more securely in context than they had been when I was playing the originals in ignorance of what they were.”

Shrinking resources throughout the academic world endanger the promise of work by sound detectives like Feaster. He’s providing heretofore unimaginable access to old sounds — one recent example is a collection of amateur “home” cylinder recordings — but he’s quick to note that the funding for such projects often falls between departmental cracks. And though specialty labels like Dust-To-Digital, with whom Feaster has collaborated, are finding ways to place this work within the realm of the music industry, their commercial prospects are limited by the esoteric nature of the work.

“The interdisciplinary field of ‘sound studies’ is booming at the moment, and that’s brought with it new interest in the history of sound media, but the academic institutional resources and incentives for a graduate student (say) to specialize in historical ‘sound-recording studies’ as someone might specialize in historical ‘film studies’ aren’t really there yet,” Feaster commented. “The intensive critical study of historical sound recordings doesn’t have a secure academic home — one where it doesn’t have to justify itself anew from scratch at every turn in terms of some other discipline. It deserves one.”

“Instant access to wide catalogs favors skimming the surface — there’s so much you want to sample you don’t bother to dig deep.” –Stephen Thomas Erlewine

Meanwhile, non-academic archival ventures face competition from unstructured but highly appealing platforms like YouTube, whose organizational forces are mostly fans who often get contextual information wrong, or streaming services, who tend to appoint celebrities and industry tastemakers, not historians, as curators. (Rhapsody, the oldest of the services, is an exception, employing working critics to write reviews and make playlists.) Most streaming services license artist overviews provided by Rovi, the entertainment data monolith whose properties include All Music Guide, or AMG, the Net’s primary music encyclopedia since 1991. AMG is a high-quality site with content written by “a hybrid of historians, critics and passionate collectors,” wrote Stephen Thomas Erlewine, Rovi’s Senior Editor for pop music. The quality of the writing and research is high, but because it seeks to be exhaustive, AMG doesn’t engage in the honing process that has defined most critical endeavors within music journalism, instead addressing lesser-quality compilations alongside key releases. On the AMG site itself, this is extremely useful — a well-informed listener will keep it open in a browser to check quality control while streaming from other sites or services. But when Rovi’s material migrates to the services themselves, the frame often disintegrates, and it’s hard to tell one release from another.

“We attempt to see how a recording fits into its era and how it plays outside of it. This applies to the written work as well as the behind-the-scenes editorial work where the Rovi staff sorts through credits and discographies, keeping things as clean as possible,” Erlewine wrote. “We occasionally make the effort to sort through compilations and mark ones that are re-recordings, but there’s not really a major market for this. Rovi also keeps individual database entries for all reissues because often each edition of What’s Goin’ On or Pet Sounds remains on the marketplace. A similar situation occurs on streaming services, which leads to duplicate listings in a discography. Spotify has gone through great effort to clean up these discographies, but for less prominent artists or ‘heritage’ acts, it can still be a mess: The Everly Brothers have proper albums in the compilation section and wrong dates scattered throughout, and Doug Sahm is littered with re-recordings and bad dates.” Plus, heritage artist like Sahm often suffer from catalog gaps. “There are huge chunks of [the late Texan’s group] the Sir Douglas Quintet’s catalog not on Spotify,” Erlewine observed. “Doug is a pretty big cult act, so that’s a good indication that others on his level or below aren’t being well-serviced digitally, and perhaps they’ll never be. And if they’re not part of the conversation, even in a small sense, don’t they run the risk of being edged out of history?”

Erlewine sees these gaps as both cause and symptom of the current online-archive browser’s impulse to go wide, but shallow — to be “tactical” about discovering older music, to reinvoke Marshall’s description. Erlewine explained, “Older collectors would go deep into styles and labels, keeping track of the catalog of a particular imprint, digging through crates and trading albums/singles in order to assemble their collection — a process that inevitably produces a more discerning ear because you’re spending more time refining your taste. Instant access to wide catalogs favors skimming the surface — there’s so much you want to sample you don’t bother to dig deep.”

“Streaming music has the potential to enable consumers to curate a multiplicity of alternative constructions of pop music history that deviate from the Rolling Stone master narrative.” –Daphne Brooks

If collectors and powerful canonizers like Jann Wenner and his staff at Rolling Stone magazine helped shape the classic rock canon — what Erlewine calls “Elvis-Beatles-Dylan-Stones-Pistols-Michael Jackson-Bruce-Prince-Nirvana” — the freer space of the streamed web has allowed for radical revisionism. Along with hip hop’s emphasis music practices like sampling and remixing, which allow for each participant to reshape the canon through visionary manipulation, streaming culture’s nonhierarchical structure is always putting forth new versions of the same old music stories.

“Streaming music has the potential to enable consumers to curate a multiplicity of alternative constructions of pop music history that deviate from the Rolling Stone master narrative,” wrote Daphne Brooks, Professor of African-American Studies and Theater Studies at Yale and the author of a forthcoming history of African-American women in popular music, in an email. “On the other hand, there’s often no context and/or erroneous information about the music that’s being posted, which is both fascinating and a problem! We need someone to start collecting all of the mythologies generated by ad-hoc annotations on YouTube, because that erroneous information is its own kind of historical narrative — why and how do people end up generating false narratives about musical texts?”

The effect on students, Brooks says, is that they’re often highly informed about popular music and its contexts — but that understanding can be scattershot, idiosyncratic, “weird. It’s less uniform, which is good if we’re pushing back against canonical epistemologies,” she wrote. “But also they have knowledge with bizarre pockets. So, for instance, many of them could say that Diana Ross looks like [the British model] Twiggy on the cover of her first solo album, but they can’t tell me when the Montgomery Bus Boycott took place.”

Erlewine expressed similar concerns. AMG, at first a deliberate attempt by founder [and Erlewine’s uncle] Michael Erlewine to broaden the scope of album guides whose authors openly scorned pop acts like ABBA and fetishized rock stars like Bob Dylan, has come to stand for the values of those old-fashioned collectors who love the minutiae of music history, and who helped shape the rock, jazz and pop canons. Erlewine is fond of those hard-working music lovers, though he see their limitations: the elitist tendency to fetishize rare objects and a certain unwavering certainty about what music should last. “This crew of collectors/fans is unified by passion, but also a perhaps too strict definition of what qualifies as canon or not,” he wrote. “Now, we roughly have two kinds of curators: aggregators of new music, and the kinds that do this fuzzy history, which winds up skimming the surface, often offering superficial or specious connections. To me, there often doesn’t seem to be as strict standards as there were for previous amateur curators. The standards are breaking down, possibly because there is so much music to sift through, possibly because all the niches are so small that there are no authoritative voices anymore.”

Despite his reservations, Erlewine sees value in the way streaming music creates a veritable web of musical histories, none necessarily overshadowing the other. “I do appreciate the perspectives of critics or fans who hear albums outside of accepted critical dogma or history — they can draw connections and conclusions that are quite insightful and imaginative.”

Ultimately, to serve not one true story of music history, but the open dialogues among a constantly expanding set of storytellers, the streaming Web does need organizing forces; but those forces must remain flexible and responsive. Official archivists are beginning to realize this. Sonnet Retman, co-director (with Michelle Habell-Pallan) of the Women Who Rock oral history archive at the University of Washington, which collects and produces material documenting the history of women making music in the Pacific Northwest and beyond, employs the word “messy” to describe the intention behind that project. “We hope that when a visitor to the archive looks for a particular person, she or he will see other interviews that are compelling, and that this browsing activity may create a more organic, haphazard and ‘messy’ set of connections for the user, like the browsing that happens when searching the web and locating material that is not archived in any formal sense,” she wrote in an email. “From this angle, the archive will always be profoundly incomplete — at best, a fluid repository indicative of relationships, ‘networks,’ stories still in the making. All of this is to say that the archive has a point of view, a politics, as well as a set of institutional and material constraints around format, labor and funding.”

Every music fan discovering, learning, or adding to an archive also has a point of view, these manifold perspectives not filling up one archive, but continually pushing against the bottoms and sides of our preconceptions of music history until those boundaries seem utterly porous. The musician and scholar David Grubbs captures the potential of archival streaming music best, perhaps, in his 2014 study of John Cage and the recorded avant-garde, Records Ruin the Landscape. Grubbs employs the metaphor of the hoard — the collector’s ultimate pleasure and deadly sin. But this hoard wants all fingers to touch it.

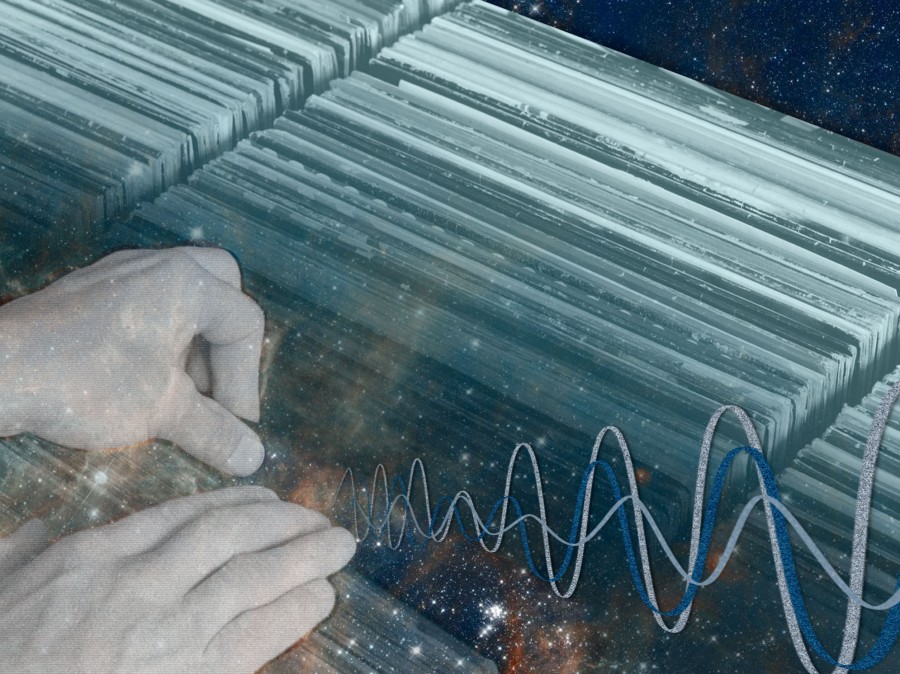

“When the total hours of one’s hoard of recorded music are no longer determined by available physical space, the stockpile — the invisible, nearly weightless stockpile — can grow exponentially,” writes Grubbs. “But a funny thing happens. Because of the trajectory of technological developments with regard to ease of access; because of the suddenly no-insane desire to be able to lay hold of any recording whatsoever; and because of the awareness that one’s lifetime minus the time represented by music that one might wish to hear leaves you with a negative sum, the stockpile comes to be held collectively. It’s everyone’s hoard.”

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))