You might not know his name, but if you’ve kept up with avant-rock music even slightly over the last 30 years, you’ve probably heard his work: Martin Bisi is a producer, engineer, studio owner, songwriter and musician with a musical résumé long enough to impress any album collector.

Bisi helmed the recording console during the recording of Herbie Hancock’s seminal Future Shock, which featured the landmark sounds of “Rockit,” and he manned the faders during Afrika Bambaataa’s “Shango Message” sessions. He’s produced records for Sonic Youth, Swans, The Dresden Dolls, Bill Laswell, Arto Lindsay, John Zorn, Lydia Lunch, William Burroughs and Ginger Baker, and he’s worked in varying capacities with Brian Eno, Iggy Pop, White Zombie, Helmet, Boredoms, Cibo Matto and filmmaker Jim Jarmusch (on the soundtrack to Down By Law).

Bisi co-founded Brooklyn’s BC Studio in the early 1980s with Laswell and Eno, and he still owns and operates the facility. It was recently the subject of a 2014 documentary called Sound and Chaos: The Story of BC Studio, featuring interviews with many of the musicians he’s worked with over the years.

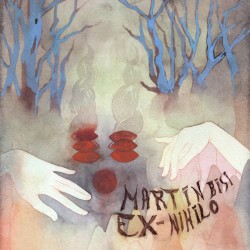

I talked to Bisi in advance of a local show he plays March 7 at Takoma venue Electric Maid in support of his 2014 release, Ex Nihilo. The following day, he shows the BC Studio documentary and performs at the Windup Space in Baltimore. A man of many interests, he talked gentrification’s impact on music, the religious experience for atheists and learning to accept your own artistic influences.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Bandwidth: In your recent documentary, you talk about the challenges of gentrification facing your studio. Is it still operational? Are you still holding out?

Martin Bisi: Yeah, I’m at home now, above the studio. We’re stable-ish, we’ve got about two or three more years I think. The value of the location increases constantly, and that’s the reason I’m staying put. People have asked me why I don’t get proactive and leave, but finding a space like this is more and more rare.

So you’re still getting studio work?

Yeah, it’s actually less bleak now than it was when we made the film. There’s been a resurgence of people caring about making albums. Just like with vinyl, I thought it was over, but it’s not. I thought it was going away as a culture.

Have you seen a recent increase in concern about fidelity, or a recent fondness for recording studios, too? Do you think projects like Dave Grohl’s Sound City have made an impact?

I haven’t seen Grohl’s documentaries yet, but I’ve been impressed at how they approach specific cities and local scenes. Even a city like Asbury Park, New Jersey, there’s been so much great music from there. It’s in the shadow of New York, but it’s a mysterious, organic community thing that makes a scene work. People tend to put all the credit on certain big names, but it’s everything — infrastructure, clubs, fans, journalists.

You’ve obviously worked with a huge number of artists over the years as an engineer. How has that impacted your own songwriting?

You’ve obviously worked with a huge number of artists over the years as an engineer. How has that impacted your own songwriting?

Well, with the album Sirens of the Apocalypse [from 2007], I was kind of mocking myself and my influences. It was a reaction to working with intense people like [Michael] Gira [of Swans] and [Bill] Laswell, like I was trying not to be like them.

I used to have the nickname “The Contrarian” among my friends. Anything I was a part of, I would try and find problems with it, whether it was feminism or Democrats or whatever. In 2009, things changed. My friends would maybe call it my “freak out.” I stopped being a contrarian, I started striving for solidarity both musically and politically. I realized I can’t afford to be a continuous naysayer, and I started actively looking for things that work.

So now my music is darker and has more gravitas. Maybe it works better that way. Maybe I should’ve been doing this all along. Ex Nihilo has more experimentation and more crazy sounds than previous records. I didn’t care about sounding like someone else. I let my songwriting be influenced by bands I’ve worked with and by our shared values.

I actually shamelessly aim to please my peers. Sometimes I’ll do something a certain way because I think, “Oh, if I do it that way, Lydia Lunch will like it.” Sometimes I think we really just make records to please each other.

New York and D.C. have both experienced a level of gentrification that would have been unthinkable only 10 or 15 years ago. How do you feel like that has impacted outsider music?

I accidentally fell into kind of being an activist with gentrification. New York has been pretty resilient though, despite CBGBs shutting down. It takes more than a few clubs closing to kill a scene. But I do think it’s important for the country to have actual cities. If nothing else, because it’s hard to put something back once it’s destroyed. Boston has been screwed — it’s gotten really hard to play there.

On Ex Nihilo, there are a lot of lyrical references to sacred words, and there are choir-like groups of voices alongside operatic vocals that seem to hearken to sacred music. What brought that about?

I’m a Materialist Atheist. I don’t believe in any life force that can’t be explained, and I’m not a spiritual person. Yet, I still possess in my brain all the building blocks for religion or belief in God. That part of me still works. Religion and focused, intense belief create profound works of art. It actually feels good to believe in things. In fact, I feel like I have a fate, even if I don’t intellectually believe it.

When large groups of people come together and chant, like at the Ferguson protests — which were actually more musical than the Occupy protests — there’s a certain feeling, even if it’s not a belief. So, I don’t deny the experience of religion or God, I just recognize it for what it is. The protests I was part of were actually the reason for the group vocals in Ex Nihilo. I’m getting older and taking the long view. I like participating in the human arc of history. It’s like being part of something dramatic and ancient.

Martin Bisi performs March 7 at 7 p.m. at The Electric Maid in Takoma and March 8 at 8 p.m. at the Windup Space in Baltimore.