Controversy over stage diving may quiet down one day. But stage diving will probably have to die out first.

The concert-going ritual—apparently still huge with Fishbone, Skrillex and tattooed young men everywhere—found itself back in the spotlight last week, when California pop-punk band Joyce Manor stopped an attendee from stage diving during the band’s show in Jacksonville, Florida. A video from the show captures Joyce Manor frontman Barry Johnson yanking the guy out of the crowd and chastising him for leaping onto a woman only part his size.

Predictably, critics began to creep out of the woodwork, calling Johnson less than masculine and unpunk for taking a stand against the practice. Johnson responded in part by tweeting the serious injuries he’d seen on tour—implying they were caused by stage diving and other punk-show tomfoolery. All of the injured parties were women, he wrote. (Update: After another confrontation with a show attendee in Houston, Johnson addressed the issue again on Facebook.)

To a segment of D.C. music fans, this debate isn’t new. There was a time when local punk rockers became bitterly divided over the related issue of slam dancing—and it’s a divide that dogs D.C.’s punk scene to this day.

Black Cat’s Dante Ferrando remembers when D.C. punks battled over moshing and what to do about it. “There was a split in the scene over how to deal with this,” says the club owner, who played in punk bands Iron Cross and Ignition in the 1980s and Gray Matter in the 1980s and ’90s. Back then, D.C. shows could turn violent, he says, and a faction of the community got sick and tired of it. That malaise eventually led many bands—but most famously, Fugazi—to repeatedly speak out against moshing and other aggressive behavior at shows.

Now when bands ask fans to curb their violent dancing, they’re chided for emulating that preachy band of grandpas, Fugazi. Screaming Females reportedly got this treatment when they asked a rowdy crowd to chill out during a 2011 show at SUNY Purchase. Fugazi’s public rejection of slam dancing still feeds some people’s distaste for the band, not to mention D.C.’s overall reputation as a city that hates fun.

“A lot of people saw the Fugazi Instrument movie where Ian MacKaye throws a fan out of a show for moshing,” says Metal Chris, who runs DCheavymetal.com. He says that image helped D.C. become known for having “boring and docile concert audiences.” He sees no problem with fans going nuts at shows—as long as it’s the right setting. “If a band is high energy, high intensity, and you don’t want to deal with that kind of behavior, then you should probably stand near the back.”

To some extent, Ferrando understands where slam-dancing advocates are coming from. “When people see their rock gods act like mom and dad, it can be a real bummer to them, I guess,” he says. But he adds that it’s better for bands to set the rules early rather than give a pass to violence and risk attracting more of it. “If you don’t take steps to control it, it will become whatever it becomes—and you will lose your ability to have any control over your crowd,” he says. “You could end up with an audience you don’t want to play to.”

“If you don’t take steps to control [violence at shows], it will become whatever it becomes—and you will lose your ability to have any control over your crowd. … You could end up with an audience you don’t want to play to.” —Dante Ferrando

The club owner speaks from experience. “With Iron Cross, we developed some fans that would cause lots of trouble,” he says. “We lost control of our audience at some point and they started to define the band.” When Ferrando left Iron Cross in 1983, he says it was partly because he’d grown sick of fans who felt they knew more about what the band stood for than he did.

But what band wants to take the risk of yelling at fans and alienating its audience? It’s not exactly good PR (though sometimes it produces funny T-shirts). “From a performer’s standpoint, no one wants to police the crowd at their own shows,” says Priests singer Katie Alice Greer. “But maybe even more so, no one wants to actively facilitate an environment for this kind of idiocy.”

Ferrando says most rock bands probably worry more about growing their fanbases. “It’s a tough one, because the average band just wants to get bigger and doesn’t think about it that much,” he says. “I think it’s very easy to get sucked into trying to get more people out to your shows, and that’s the primary goal—without trying to be selective about who is coming out to your shows.”

Meanwhile, tensions simmer between bands who encourage slam dancing and the risk-averse clubs that host them. Metal Chris says he saw that tension play out during a Municipal Waste show at D.C.’s Rock & Roll Hotel in 2010. Club security was “throwing out stage divers,” he says, and the Richmond thrash-metal band fought back. The group stopped playing and protested the security measures, “creating an odd vibe for the show that basically felt like the band and its fans versus the venue and its staff.” According to the blogger, Municipal Waste’s Tony Foresta invited the whole crowd onstage, saying “They can’t throw us all out!” (Neither Municipal Waste’s label nor Rock & Roll Hotel booker Steve Lambert returned a request for comment.)

Coke Bust drummer Chris Moore recognizes the importance of letting showgoers express themselves, but he says they should still follow some basic rules. “You shouldn’t dive feet first, you shouldn’t dive into a small crowd, and you should try and avoid people who are a lot smaller than you,” he says.

Greer offers a similar guideline. “People who want to consensually punch and jump on each other should really be doing this in a pit behind the people who are dancing to and watching the show,” she says. “I hope this gets written into the next edition of the show-attendance etiquette handbook.”

But what happens when a new generation comes along and doesn’t realize there’s an etiquette handbook—or simply chooses to flout it? What if the venue doesn’t have security? What choice does a band like Joyce Manor have? Fugazi’s MacKaye (who declined to comment for this story) has compared the scenario to a dinner party gone down the tubes.

“It would be if like I was having you over for dinner and someone started stabbing you with a butter knife,” MacKaye told NPR’s Ask Me Another. “I would encourage that person to stop. It just seems obvious.”

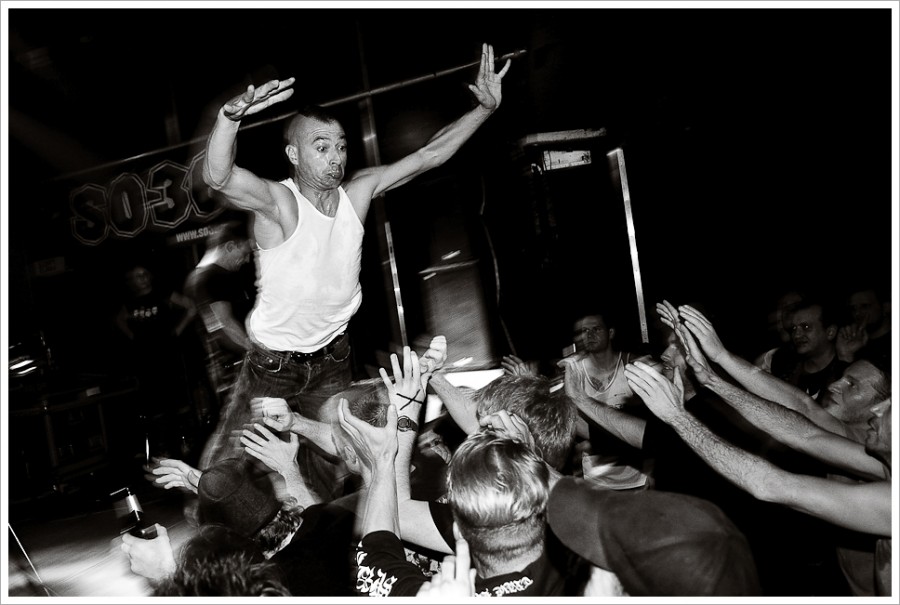

Photo by Flickr user Montecruz Foto used under a Creative Commons license.

Pingback: Arts Roundup: Bronze Bodies Edition - Arts Desk()

Pingback: District Line Daily: D.C.’s Problematic Safe Drivers - City Desk()