On a narrow road off Rhode Island Avenue in Hyattsville, Maryland, a plain, squat building sits nestled in a grubby industrial zone. Surrounded by a wood-plank fence, the structure dwells just beyond a cluster of auto-repair garages and scrap shops that’s bisected and isolated by railroad tracks. From the outside, the building fits in: It’s unremarkable, even ugly.

Behind the fence, signs of creative life flicker. Inside the building, up a flight of stairs, producers and rappers bump beats in a two-room recording studio. Outside, a PA and a stage are planted in the yard next to a garage equipped with a DJ booth, old couches and bar stools. Elaborate street art tattoos the fence and the garage’s interior walls. Teenagers are out here, smoking cigarettes in camp chairs. They’re waiting for a show to start.

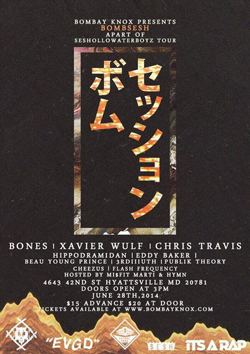

Since June, this has been the headquarters of Bombay Knox, the hip-hop promotion and management group that has carved its own space in D.C.’s small but growing hip-hop scene with an approach that, at least here, is usually associated with punk rock: It books low-cost all-ages shows, often at unconventional spaces like this one.

It’s difficult to understand the importance of Bombay Knox by describing what it is. Technically, it’s a business that offers a range of creative services—from artist management to promotion to videography to recording. But its reputation is staked on its hip-hop concerts, which it hosts at places as unrefined as an Adams Morgan auto shop and as professional as U Street Music Hall. As local hip-hop begins to produce national stars—Wale, Fat Trel—the group is positioning itself to foster even more homegrown talent in a city that has never been seen as a hip-hop capital.

It’s difficult to understand the importance of Bombay Knox by describing what it is. Technically, it’s a business that offers a range of creative services—from artist management to promotion to videography to recording. But its reputation is staked on its hip-hop concerts, which it hosts at places as unrefined as an Adams Morgan auto shop and as professional as U Street Music Hall. As local hip-hop begins to produce national stars—Wale, Fat Trel—the group is positioning itself to foster even more homegrown talent in a city that has never been seen as a hip-hop capital.

The architect behind Bombay Knox is Jesse Rubin, a soft-spoken D.C.-area native with a robust red beard. Rubin handles almost all of the group’s noncreative business: He books the shows, answers emails and runs the Twitter account. He conceived Bombay Knox in 2011 while studying film at DePaul University in Chicago and managing hip-hop production team Odd Couple.

“There was a lack of these local shows,” says Bombay Knox founder Jesse Rubin. “There wasn’t a real, solid underground scene [in D.C.].”

Rubin spent his time after graduation floating around New York’s underground hip-hop world, shooting music videos and working in artist management for members of Joey Bada$$’s Pro Era rap crew. The scene felt too crowded for his taste—he had to split management duties and he wasn’t getting big-picture control of artist booking and promotion—but he liked its energy. “In New York, there are cool underground shows every day,” he says. “You can see people from the area and from outside the area that put on cool affordable shows.”

When Rubin returned to the D.C. region in 2012, he realized he could start his own thing in a city that has no equivalent to what he saw up north. “There was a lack of these local shows,” he says. “There wasn’t a real, solid underground scene.”

Bombay Knox hosted its first show in spring 2013 at the now-defunct Georgetown gallery MOCA DC. The format—a cheap, all-ages show featuring young, occasionally unpolished rappers—has changed little since.

Bombay Knox hosted its first show in spring 2013 at the now-defunct Georgetown gallery MOCA DC. The format—a cheap, all-ages show featuring young, occasionally unpolished rappers—has changed little since.

The group rarely charges more than $5 to $15 for its events, and many are free. So far, it’s maintained a busy schedule—unlike other local independent hip-hop promoters that book shows sporadically or have fizzled out completely. The group has put together more than 30 events in the last year and a half. Last week, it co-hosted a video game tournament and show with a local hip-hop collective called Kool Klux Klan. Admission price: $5.

Booking cheap shows isn’t always a money-maker for Rubin. “I go into the show knowing my best-case scenario is breaking even on expenses,” he says. “But for me, even if I lose some money, in terms of building up the brand it’s not a bad investment.”

Some promoters might choose to recoup their losses by charging artists to perform on their shows. But Bombay Knox claims to offer an alternative to pay-to-play, which many consider predatory. Pay-to-play is fairly common in local hip-hop and across the country, according to some reports—and Rubin says he stays away from it. For young, cash-strapped artists on the rise, that can make all the difference.

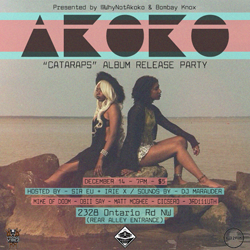

The steady supply of shows has helped Bombay Knox raise its profile and grow: That creaky stage in Hyattsville has hosted acts with healthy followings outside of D.C., like Mr. MFN eXquire, Bones and Drake-endorsed freestyler Nickelus F. Some of the artists it manages have made an impression online, too: Gaithersburg rapper Uno Hype has appeared on tracks with massively popular rappers Smoke DZA, Joey Bada$$ and Chance the Rapper, and he’s been praised by tastemaking outlet Complex. Another Bombay act, D.C.-based Akoko, has sharp ‘90s flows and tight harmonies that have earned the duo thousands of YouTube views.

Rubin hasn’t done everything on his own. He holds down Bombay Knox’s business affairs while a coterie of associates help out with things like merchandise and event art. Manny Phaces handles some of Bombay’s sound engineering. Bombay’s creative director, Kevin Chambers—also a producer known as Flash Frequency—cranks out the group’s clean and modern photos and posters, and—yes—GIFs.

Rubin and his associates have gone the DIY route mostly out of necessity. He suspects that some spaces haven’t wanted to work with him because they associate hip-hop with bad news. Bombay’s time at MOCA DC ended quickly: Rubin says some neighborhood restaurant owners, who were already upset with the venue’s nude art parties, complained that the gallery’s hip-hop shows hurt their businesses.

“When people hear rap or hip-hop, they have this assumption that it’ll be something like Fat Trel,” he says, referring to the rising D.C. rapper with a tough reputation. “Then they see something and they’re like ‘Oh, trouble.'”

“When people hear rap or hip-hop, they have this assumption that it’ll be something like Fat Trel,” he says, referring to the rising D.C. rapper with a tough reputation. “Then they see something and they’re like ‘Oh, trouble.'”

Other venues haven’t had the same reaction. In early August, D.C. go-go artist turned rapper Yung Gleesh headlined a wild Bombay Knox show at U Street Music Hall with Uno Hype, Sir. E.U. and Flash Frequency. It was Bombay’s biggest event yet. Meanwhile, Rubin says he’s already in talks with even bigger venues.

For small gigs, the Hyattsville building—which Rubin took over from a friend who had hosted parties there—will do for now. The Akoko show in mid-July drew around 50 people. It was a small turnout by the group’s standards, but the crowd didn’t seem to mind, as it vacillated between head-nodding and moshing. When Bones played the spot in June, multiple guests said it attracted close to 300 people.

Bombay Knox sees the Hyattsville studio as its key to profitability. It offers in-house artists a means to crank out more music, and studio fees could help fund future endeavors. It’s been a blessing for Bombay’s current artists, too; Sir E.U. has been finishing up his album Madagascar there while Rubin works on finalizing details for the first Bombay Knox compilation. Eventually, Rubin wants to ease off on hosting events at the space, and transform the studio into its primary operation. The venue isn’t easily accessible by public transportation, and Rubin says that noise complaints have brought police to the venue before.

But while Uno Hype, Chambers and Phaces hang out in the studio that July night—chatting about Cuba Gooding Jr. and watching Cosgrove’s video interview with Complex—it feels like this cheap, raw space could be the incubator that talented but untested artists need to grow.

Top photo: From left to right, Kevin Chambers, Ace Cosgrove and Manny Phaces in the Bombay Knox studio.