Sean Michaels has been on a quest for a few good theremin players.

“I’ve spent the past several months scouring the landscape of America for thereminists. They’re a very rare breed,” says the Montreal-based novelist and music blogger. “But on the other hand, they’re surprisingly easy to find. When somebody plays the theremin, other people remember.”

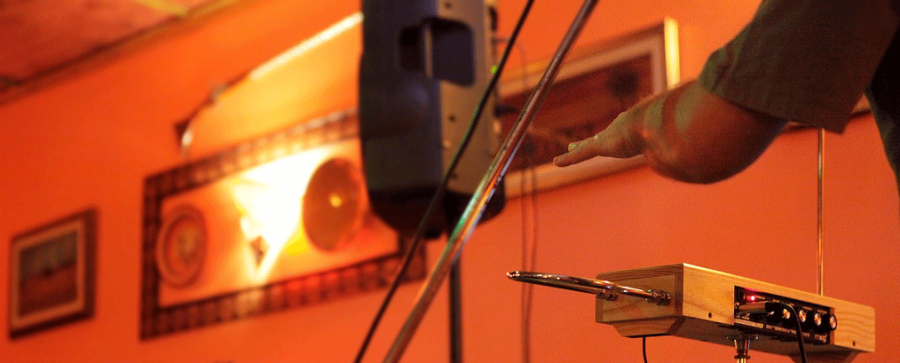

Michaels began tracking down theremin players in order to recruit them for his book tour, a two-week jaunt through the United States that touches down at D.C.’s Kramerbooks Friday night. In April he published his debut novel, Us Conductors, a partially fictionalized work based on the life of Lev Sergeyevich Termen, also known as Léon Theremin. He was the Russian inventor who, in 1918, devised the enchanting instrument that is played by waving one’s hands between two antennas, repositioning them to modulate pitch and volume.

Michaels began tracking down theremin players in order to recruit them for his book tour, a two-week jaunt through the United States that touches down at D.C.’s Kramerbooks Friday night. In April he published his debut novel, Us Conductors, a partially fictionalized work based on the life of Lev Sergeyevich Termen, also known as Léon Theremin. He was the Russian inventor who, in 1918, devised the enchanting instrument that is played by waving one’s hands between two antennas, repositioning them to modulate pitch and volume.

Us Conductors depicts 20 years in Termen’s life, tracing his days as a humble scientist, his glory years as a lauded inventor, and some of his extensive time in a Russian prison for scientists. But it also tells a tale of unrequited love: Termen pined for Clara Reisenberg, a beautiful young violinist who later won fame as a master of the instrument Termen invented. She turned down Termen’s marriage proposal, opting to wed attorney Robert Rockmore and use his last name.

Michaels says Rockmore, and the strange instrument she played so remarkably, formed a deep well of inspiration for him. “For the last 10 years I’ve been enchanted with the theremin. It’s such a crazy object and such a crazy instrument,” he says. “It’s insane to watch someone playing it and how it seems like—you don’t understand what’s happening.” Rockmore played the theremin so well, he says, “it sounds almost like an opera singer singing.”

Rockmore’s was a difficult skill to master, Michaels says. He’s tried it himself, to mixed results. (In his defense, he’s only been attempting it since last winter, when MOOG sent him a theremin.) “You have to be very, very precise. The smallest little movement or breath or step that you might take can change the note by a third of an octave,” he says. “There’s something strange about playing an instrument that you’re not tethered to in any way.” Just waving one’s hands around takes a lot of guesswork, he says, and intuition not too different from the kind we need to engage with other people without, well, mucking everything up.

“I think in a lot of ways [playing the theremin is] closer to the way we have relationships with people,” Michaels says. “You don’t always know exactly where you stand with them… There’s no gauge saying ‘You’re exactly here. You’re exactly there. You are officially in love. You are not.'”

For his Friday engagement at Kramerbooks, Michaels has invited a local thereminist to demonstrate the instrument. The guest musician happens to be one of the region’s best-known players—and also a kind of “theremin hacker,” Michaels says. He’s Arthur Harrison, owner of the Silver Spring company Harrison Instruments. Harrison’s self-designed theremins range in price from $279 to $1,300—and he makes them for righties and lefties.

If there are any stereotypes of theremin players—like there are for, say, drummers and bass players—Harrison might fit one of two typical profiles. “I can imagine two different stereotypes,” Michaels says. “One is this slightly poindextery mad scientist musician who likes the physics of this weird device.” The other, descended from Clara Rockmore, is an “elegant younger woman.” In fact, he says, in Europe, there’s even a minor theremin craze going on among young women.

Yet despite the years of obsession and research that went into writing Us Conductors, Michaels says he’s somewhat behind on the latest theremin trends.

“It’s funny, because as much as I’ve become educated a little bit about the contemporary theremin scene, I’ve spent most of my past five years thinking about theremin in the roaring twenties—a century ago,” he says. “So I’m actually a little bit out of touch. But I’m trying to bone up.”

Sean Michaels and Arthur Harrison appear at Kramerbooks at 7 p.m. Friday night.

Photo by Flickr user giulioescalona used under a Creative Commons license.

Pingback: Arts Roundup: Fort Reno a No-Go? Edition - Arts Desk()

Pingback: District Line Daily: The Other Local Soccer News - City Desk()