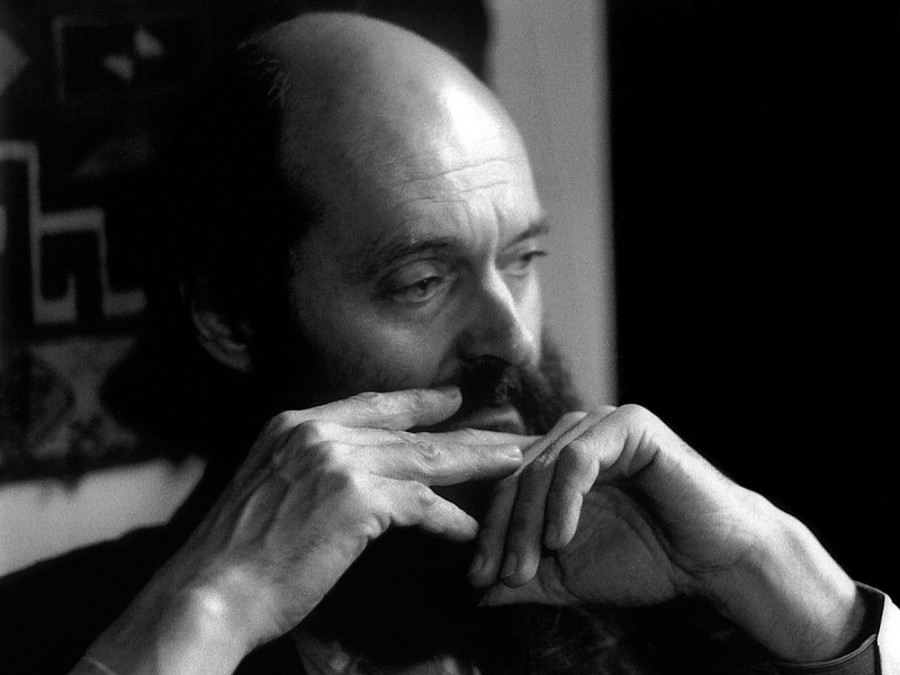

Arvo Pärt is one of the few living composers to find popularity beyond the borders of classical music. R.E.M.‘s Michael Stipe and Bjork are big fans. Although the 78-year-old musician usually shies away from acclaim and the media, he is currently attending a festival of his music in New York and Washington, and he made time to talk about his music, bike riding and bells.

Pärt is a major composer, and I was a little nervous meeting him. So I brought along a bell for good luck. I set it on the table between us and gave it a little tinkle.

“Oh, this is a good beginning, thank you,” he said in his heavily accented English.

Pärt likes bells, literally and figuratively in his music. He also likes space and silence. Fans tend to use words like “timeless” to describe his contemplative music. But for Pärt, time has deep meaning. In conversation, as in his music, he takes his time to unclutter his thoughts. They come out like poems.

“Time for us, is like the time of our own lives,” he says. “It is temporary. What is timeless is the time of eternal life. That is eternal. These are all high words, and so, like the sun, we cannot really look at them directly, but my intuition tells me that the human soul is connected to both of them — time and eternity.”

Pärt has gravitas to burn. But he didn’t start out that way. As a kid in Soviet-era Estonia, he practiced on a battered old piano and rode his bike around the town listening to Finnish radio broadcasts. I told him that I strapped a transistor radio to my bicycle when I was a kid. “It’s very interesting,” he responded, with a slight twinkle in his eye.

Early on, Pärt wrote thorny, atonal music in the style of the day. But in 1968 he hit a wall. He went nearly silent for eight years, and when he returned, it was with something completely different. Slow, pure, simple, yet powerfully focused is how conductor Stephen Layton describes the music: “If you had to give an aesthetic for his compositional output, less is more is certainly it,” Layton says.

A choral specialist, Layton has recorded two albums of Pärt’s vocal works (a third is scheduled for this fall). Layton says after the complicated music that dominated the mid-20th century, Pärt’s new style, with nods to Gregorian chant and Renaissance music, wiped the slate clean. Part of Pärt’s breakthrough, Layton says, came from hearing just three notes in a supermarket.

“Over the public address system one hears the sound ‘doo, doo doo’ ” — Layton sings three descending tones — “‘Could so-and-so please go to till No. 25?’ Now that sound is called a triad in music, but it’s actually the building block of all music in the Western world.”

Pärt realized the beautiful simplicity of the triad and ran with it. He called his newfound style “tintinnabuli,” a word referring to little tinkling bells. Another ingredient in the recipe is silence.

“On the one hand, silence is like fertile soil, which, as it were, awaits our creative act, our seed,” Pärt says. “On the other hand, silence must be approached with a feeling of awe. And when we speak about silence, we must keep in mind that it has two different wings, so to speak. Silence can be both that which is outside of us and that which is inside a person. The silence of our soul, which isn’t even affected by external distractions, is actually more crucial but more difficult to achieve.”

Pärt’s musical combination of awe and silence caused German record producer Manfred Eicher to pull off the autobahn when he heard Tabula Rasa on the radio. “It was music you discover that makes you speechless, breathless and thoughtful,” Eicher recalls. “Yes, I wanted to be closer to this music.”

It took Eicher, the founder of ECM Records, six months to track down Pärt and a few more years before he released Pärt’s first ECM album in 1984. The album, which included Tabula Rasa for two solo violins and chamber orchestra, opened the door to the West for Part’s music. Thirteen records have followed on ECM alone, with albums appearing on other labels as well.

Pärt’s austere music and his penchant for religious texts (he embraced Eastern Orthodox Christianity in the 1970s) have lent him a certain reputation, says countertenor David James of the Hilliard Ensemble, a group that began championing Pärt’s music in the 1980s.

“A lot of people have this impression,” James says, “that he’s a bit of a recluse, sort of monk-like. Yes, when you see him. But as soon as you speak to him and get to know him, I tell you, he has the most wonderful sense of humor and a most engaging personality.”

I asked Pärt how he likes being thought of as a mystic. He laughs.

“Ah,” he says, “that is the last thing I want to be.”

Pärt turned out to be exactly as James described him — engaging and personal. And at the end of the interview, he even said we had something in common. That’s when he held up his hands, as though he were holding the handlebars of a bicycle.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))

Playlist

Hear the Music

Artist: Keith Jarrett

Album: Arvo Pärt: Tabula Rasa