By now, you’ve likely seen or heard that Friday marks the 50th anniversary of the first time The Beatles set foot in America. It’s being hailed as the beginning of Beatlemania by some, an event that changed the course of history by others. In fact, the Beatles were already stars in Europe and No. 1 on American radio by the time they landed. What is often overlooked is how many times the Beatles had failed to catch on in the U.S. before 1964.

In early February 1963 — a year before the Beatles arrived in New York for The Ed Sullivan Show — Chicago DJ Dick Biondi spun a 45 from the small Vee-Jay label by a group whose name was misspelled B-E-A-T-T-L-E-S.

At the age of 83, Dick Biondi is still on the air at WLS-FM in Chicago. “I didn’t know what to think, because they were good,” he says. “Is this going to be a hit? I just played it and I liked it. And I got — not a lot of good comment, but I didn’t get any bad comment.”

Three months later, Biondi was fired, and he wound up at KRLA in Los Angeles. He played the record again there. “The phones started ringing, and the kids said, ‘Take that crap off and play the Beach Boys!’ ”

“Please Please Me” was a flop. A follow-up single, “From Me To You,” did a little better, but the Beatles version stalled when American Del Shannon, of “Runaway” fame, recorded and released his own version.

Before 1964, few British performers had made a dent in U.S. charts, so it wasn’t surprising that, given the choice to play an unknown British band or an American hitmaker’s version, most DJs went with Shannon, says Beatles historian Bruce Spizer.

“Back in the ’60s, particularly the early ’60s, we were by no means living in a global community,” he says. “Britain was this far-off, exotic place across the pond. And initially that probably worked against the Beatles in that it was considered, you know, foreign and nothing that we really need here.”

“Across the pond” the Beatles had already cracked the Top 10, but here Capitol Records, the major label with rights to distribute the Beatles in the U.S., passed on their next disc, too.

“She Loves You” wound up being released by the tiny Swan label out of Philadelphia in September 1963. Spizer says the label tried to get Dick Clark to spin it. American Bandstand was broadcast nationally out of Philadelphia. “He went ahead and had the record on his ‘rate a record’ segment. The records that did well would score in the 80s or 90s. ‘She Loves You’ scored in the low 70s.”

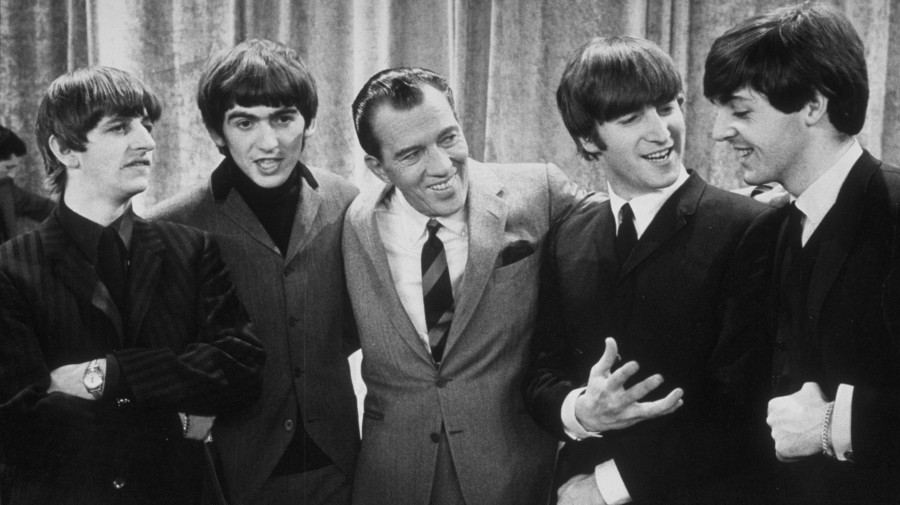

Another washout for the Beatles. The game changer for them came Halloween night 1963. The story goes that CBS variety show host Ed Sullivan just happened to be at London’s airport, when thousands of fans were awaiting the Beatles’ return from a tour of Sweden.

“Of course he’d never heard of the Beatles,” says Sullivan biographer Jerry Bowles, “but instantly he recognized that if they could get 3,000 screaming teenagers to show up at an airport in the middle of the night, they must be somebody.”

Five nights later, the Beatles got the attention of the international press by playing for an upper-crust British audience, including members of the royal family, at London’s Prince of Wales Theatre for the Royal Command Performance. Beatles manager Brian Epstein headed for New York the next day, and soon inked a deal with Sullivan. Major American newsmagazines and TV networks also did stories on the Beatles after that Royal Command Performance. One aired on CBS the morning of Nov. 22, 1963.

“Those are the Beatles and this is Beatleland, formerly known as Britain,” said the reporter, “where an epidemic known as Beatlemania has seized the teenage population, especially female.”

The story might very well have aired again that night, but at 1 p.m. CST, President John F. Kennedy died in Dallas. CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite decided to sit on the Beatles story for three weeks, while the country mourned the loss of JFK.

But by Dec. 10, Cronkite felt the country could use the diversion and re-aired the Beatles piece. Fourteen-year-old Marsha Albert of Silver Spring, Md., saw the broadcast and wrote WWDC radio requesting Beatles music. DJ Carroll James arranged to have a copy of the British release of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” hand-carried from England. He played it eight days before Christmas 1963.

The response in D.C., St. Louis and Chicago — where DJs got copies of the record from James — was so great that Capitol Records rush-released the single the day after Christmas. Beatles historian Spizer calls that move brilliant.

“Kids are not in school. And they listened to the radio in those days. There are no video games. Kids that have Christmas and Hanukkah money and Mommy and Daddy can take them to the record store, and the next thing you know ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ is a humongous hit in New York and other cities follow.”

Biondi and many others since have said America used the Beatles’ exuberance to chase away the clouds of JFK’s assassination. Since they weren’t from here, it seemed OK for the boisterous Brits to put an end to the mourning period. The Beatles were suddenly all over the radio everywhere. Capitol Records dumped a then unprecedented $50,000 into promotion, creating perhaps the first artist “street teams.”

“They were doing many creative things. Posters, all sorts of things. Giving away ‘Be a Beatle Booster’ buttons. Encouraging people to wear Beatle wigs,” says Spizer. “They got very much into it and really created the concept of marketing directly to the consumer, which of course is done all the time today, but at the time was revolutionary.”

And the Beatles’ U.S. arrival was still more than a month away. With the buzz building, NBC’s Jack Paar pulled a scoop on rival Ed Sullivan on Jan. 3 that almost derailed the Beatles express. Paar and Sullivan were fierce competitors, and Paar got Beatles performance footage from the BBC to air on his program ahead of Sullivan.

“The Beatles are an extraordinary act in England. I think they’re the biggest thing in England in 25 years,” said Paar in his report. “These guys have these crazy hairdos and when they wiggle their head and the hair goes, the girls go out of their minds.”

Sullivan was absolutely livid. And he contacted his European talent coordinator, Peter Prichard, and told him to cancel the Beatles. Fortunately a day or two later Sullivan realized that it would be a mistake to cancel the Beatles so he called up Prichard and canceled the cancellation.

And so, the Beatles arrived on Feb. 7, played two days later, and the story from there is burned into American consciousness.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))