Inside Llewyn Davis is set in the Greenwich Village folk music scene of the early 1960s. In a scene from the Coen brothers movie, the fictional Llewyn Davis sits on stage and sings a tune that Dave Van Ronk performed and recorded. Like Van Ronk, the fictional Davis has dark hair and a beard, and spent some time in the merchant marine. And the album cover for the fictional LP that gives the movie its title looks just like the real 1963 LP Inside Dave Van Ronk.

Elijah Wald, a writer and musician who took guitar lessons from Van Ronk, says that’s where the similarities end.

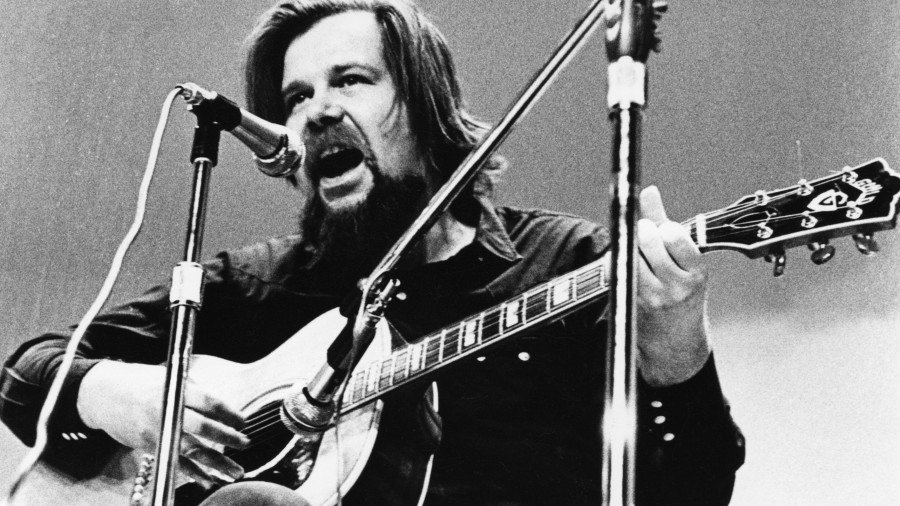

“Nothing about the character is like Dave Van Ronk,” Wald says. “He was just this huge presence. He was 6’3″, 200-something pounds.”

Wald helped write Van Ronk’s posthumous memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, which was titled after the Greenwich Village street that was home to The Gaslight Cafe and other folk clubs in the early 1960s.

“Dave was the king of that world. He really knew New York, he really knew history, he really knew music,” Wald says.

Van Ronk also knew how to tell a story, a talent he displayed on stage between songs. That talent was front and center on 2004’s And the tin pan bended and the story ended…, a live recording of his last concert.

“I have often thought back and wondered just what my reaction would have been at age 17 if someone had told me I would go through most of my life being called a folk singer,” Van Ronk said during the show. “I probably would’ve slashed my wrists.”

The performance was recorded in October of 2001, just months before he died of colon cancer. Despite what his legacy leaves behind, Van Ronk never thought of himself as a folk singer.

“What I really wanted — I wanted to play jazz in the worst way,” he said. “And I did.”

Van Ronk grew up in Brooklyn and Queens. He moved to Greenwich Village as a teenager in the early ’50s and tried to make it playing in old-time jazz bands. But he found more success singing blues and folk songs in the clubs that were springing up in the village.

He recorded a handful of well-received albums in the early 1960s. Wald says he became a mentor to younger musicians, including Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton and Bob Dylan. In fact, Dylan borrowed one of Van Ronk’s arrangements for his first album.

“He asked me if I would mind if he recorded my version of ‘House of the Rising Sun,'” Van Ronk said years later in the Dylan documentary No Direction Home. “So I said, ‘Well gee, Bob, I’d rather you didn’t because I’m gonna record it myself soon.’ And Bobby said, ‘Uh oh.'”

Van Ronk said he had to stop playing the song because people thought he’d stolen it from Dylan. He laughed in the documentary as he remembered things eventually coming full circle.

“Later on, when Eric Burdon and The Animals picked the song up from Bobby and recorded it, Bobby told me that he had to drop it, because everyone accused him of ripping it off from Eric Burdon,” Van Ronk said.

Over time, Dylan and most other fixtures of the folk scene moved out of Greenwich Village. But Van Ronk stayed put, taking on students between gigs to pay the bills.

Andrea Vuocolo married Van Ronk in 1988. She still lives in the small apartment they shared, which is packed with her late husband’s books, guitars and collections of African and Native American art. Vuocolo says her husband read voraciously, and was also a keen observer of the neighborhood.

“He used to tell stories about the village in the ’50s and ’60s,” Vuocolo says. “And there were a lot of people hanging around the clubs who were not musicians. You know, locals, a lot of petty thieves and odd characters. … He wanted to write more about the whole neighborhood.”

But Van Ronk died before he could write more than a few chapters of his memoir. Elijah Wald was able to finish the book using a combination of interviews and stories Van Ronk had told from the stage; the memoir went on to inspire Inside Llewyn Davis.

The last time the Coens built a movie around music, the soundtrack of O Brother, Where Art Thou? sold millions of copies and spurred an old-time music revival. Van Ronk’s widow hopes this movie will do the same for her husband’s legacy.

“It’s very nice to just see people finally paying attention to his work more,” Vuocolo says. “And I think that would have been great for him. Just to be noticed more, and have more people listen and understand what he was about.”

At his final concert, Van Ronk joked that there were lines around the block to see the Beat generation poets in Greenwich Village coffee houses.

“This presented a logistical problem for the owners of coffee houses — how to get people out of there, and get new people in. So they hired folk singers,” he said. “They’d get up and sing three songs. If, at the end of three songs, anybody was still seated, we could get fired. We turned the house over just like that.”

The tourists might have left, but when Dave Van Ronk started singing, the musicians stayed to listen.

9(MDAxNzk1MDc4MDEyMTU0NTY4ODBlNmE3Yw001))