Spurred by new, affordable technology, the home-recording boom of the 1980s and ’90s produced some of the most idiosyncratic music of the 20th century. When that boom touched down in the suburbs of Baltimore, weird stuff started to happen.

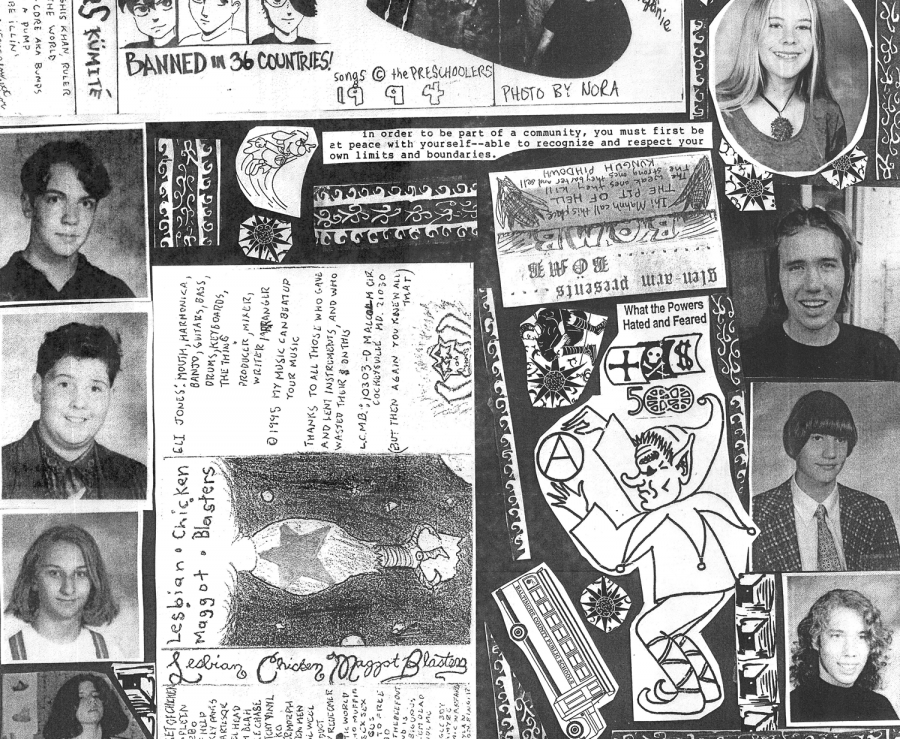

Mike Apichella was a teenager in Baltimore County in the ’90s. Early in the decade, he and his pals formed a loose music and art collective named Towson-Glen Arm after their hometowns. They rallied around a love of art, activism and the avant-garde, bridging the silly and the sincere; Towson-Glen Arm kids wrote poetry about social issues, but they also formed bands with names like Spastic Cracker and Lesbian Chicken Maggot Blasters.

In a way, Apichella and his crew followed in the footsteps of the greats of the home-recording movement, like Guided by Voices and Sebadoh. But they didn’t just do it with guitars, and they didn’t care about genre. Spoken word, funk, country, jazz, noise and ska — it was all on the table.

In a way, Apichella and his crew followed in the footsteps of the greats of the home-recording movement, like Guided by Voices and Sebadoh. But they didn’t just do it with guitars, and they didn’t care about genre. Spoken word, funk, country, jazz, noise and ska — it was all on the table.

Apichella says the Towson-Glen Arm era was marked by its participants’ “avant-garde ambitions, revolutionary politics and straight-up teenage goofiness smashing into one another in this big spectacle.”

Later, some of those same suburban kids went on to play with well-known indie-rock acts like A Silver Mt. Zion, Cass McCombs, Lower Dens and Will Oldham. Apichella became better known for his band Human Host. It wasn’t until years after the Towson-Glen Arm heyday that Apichella decided to tell the story of his hometown scene.

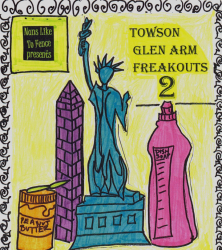

Apichella took 44 songs his Towson-Glen Arm community had produced and put them on cassette tapes. He called the compilations Towson-Glen Arm Freakouts and started releasing them in 2013. All proceeds from their sale went toward two Maryland organizations: music education nonprofit music4more and Grassroots Crisis Intervention, which provides support to people contemplating suicide.

Apichella took 44 songs his Towson-Glen Arm community had produced and put them on cassette tapes. He called the compilations Towson-Glen Arm Freakouts and started releasing them in 2013. All proceeds from their sale went toward two Maryland organizations: music education nonprofit music4more and Grassroots Crisis Intervention, which provides support to people contemplating suicide.

This spring, Apichella is sending those tapes to Europe for the first time, in an effort to “share the TGA craziness with people from far-off places.”

I recently chatted with Apichella via email about growing up in what he calls “the politically conflicted region of DelMarVa” and the lasting legacy of his crazy suburban scene.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Bandwidth: How have the tapes been received since you released them in 2013? What encouraged the upcoming European release?

Mike Apichella: For folks who never knew about Towson-Glen Arm until recently… discovering the Towson-Glen Arm stuff is a pleasant shock. Like they’re surprised to hear how contemporary the music sounds and how politically charged it was even though it was also sort of crazy and absurd.

I have to hype this record to as many audiences as I can because the music and art featured on the two TGAF comps just isn’t commercial. It’s a niche interest for people who like obscure creative work. Luckily, that niche interest is shared by record collectors and fans all over the world.

The two Towson-Glen Arm Freakouts compilations cover 1992 to 1999. How old was everybody during that time?

Roughly, the age range… was about 14 to 20. Most of the kids were high school students, or younger college-aged kids. A few older 20-somethings hung out, and even some 12-year-olds and 13-year-olds ended up in the mix occasionally.

Obviously there’s a lot of different technologies and environments captured here. How did you go about recording some of these songs?

Towson-Glen Arm records were recorded using low-budget, one-track portable tape recorders and cassette four-track recorders. A few bands recorded music on reel-to-reel tape recorders and a few recorded in studios. There’s even a tiny bit of video-tape documentation.

“Towson-Glen Arm was just a crew of smart, funny, really politically aware kids who were really psyched about subverting the destructive elements of society with art.”

What were some of your influences at the time?

A lot of the Towson-Glen Arm kids actually did have formal music training, or just had the natural ability to play classical and jazz with as much passion as they played weirder music or rock or folk or whatever. So sometimes the TGA diversity came from some of the scene’s more traditional musical/literary/visual art influences just sort of subconsciously.

I think the idea of mixing many different kinds of aesthetic concepts was one of the few really thought-out artistic goals of the scene. Many of us developed a consciousness of things like social-justice issues. This really influenced our attempt to try and make TGA a safe space for anyone and everyone who could oppose fascist/imperialist evil and all of the bad consequences associated with stuff like that.

How were these songs received then?

For the most part all this stuff was a local phenomenon. To me, Towson-Glen Arm was just a crew of smart, funny, really politically aware kids who were really psyched about subverting the destructive elements of society with art.

We had our own weird little world, but we treated it as if it were boundless, and I think that’s why it was really hard for “normal” kids and punks and stoners of the time to really find a lot of common ground with us.

It wasn’t even like we necessarily were acting against punks or preppies or whatever, it’s just that most of us didn’t even spend a lot of time thinking about what genre of music or art we were or weren’t gonna create.

How did you organize yourselves into bands?

Sometimes bands were formed at random. Some TGA bands were formed with a real preconceived concept in mind. Other bands emerged out of stuff like inside jokes.

Some of the TGA bands weren’t bands at all. Instead they were recording projects that only existed on tape and nowhere else.

Nothing really controlled what aesthetically defined a recording project and a live band. Some of the least commercial TGA stuff remained recording-only just because a lot of us knew no one would book the really extra far-out projects.

Which Towson-Glen Arm bands went on to earn fame and notoriety?

Walker [Teret] is very well-known in indie circles as a session musician, a producer and all-around musical genius. He’s played with Will Oldham, Arbouretum, and he also currently is in Celebration.

But Scott Gilmore might be the most accomplished of all the Towson-Glen Arm artists. He joined the Canadian band A Silver Mt. Zion during the early/mid aughts after he moved up north to go to college in Montreal. Scott now works advocating for and giving legal help to victims of state-sponsored torture who are from countries controlled by totalitarian regimes, so I’d say both politically and artistically Scott Gilmore’s achievements are the biggest things done by a TGA artist.

Is there any one song on these that you feel best captures what the Towson-Glen Arm scene was all about?

Absolutely! “Scott Chester, Boy Next Door” by The Preschoolers. That track is as much a document of the scene’s sense of humor and theater as it is a fine example of the kind of wild music and political influences that TGA became synonymous with. Plus, like almost half the musicians in the scene play on that track.