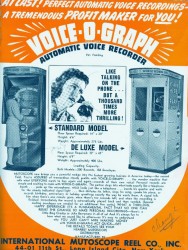

Before smartphones, before voicemail, before the advent of answering machines, the easiest way to record your voice for a loved one was to step into a Voice-O-Graph booth.

The Voice-O-Graph was a do-it-yourself recording studio the size of a small closet. Walk inside, close the door, deposit 35 cents and make a record of your own. The machines cranked out a lacquer-coated disc that held about a minute of crackling sound. During World War II, soldiers and their families swapped the plates across oceans. They felt more alive than a letter, and they didn’t clog up what was then a limited number of long-distance phone lines.

The Voice-O-Graph was a do-it-yourself recording studio the size of a small closet. Walk inside, close the door, deposit 35 cents and make a record of your own. The machines cranked out a lacquer-coated disc that held about a minute of crackling sound. During World War II, soldiers and their families swapped the plates across oceans. They felt more alive than a letter, and they didn’t clog up what was then a limited number of long-distance phone lines.

Painted advertisements on Voice-O-Graph booths promised technological wonder rarely available to regular folks at the time. “Step in! Record your voice!” “Hear yourself as others hear you!”

Voice-O-Graph booths once peppered movie theaters, arcades, state fairs and bus stations across the U.S. But with the advance of compact cassettes in the ‘60s, the machines were relegated to garages, cellars and garbage heaps — obsolete and unwanted.

But recently, Voice-O-Graphs have made a comeback. A 1947 model appeared on a 2014 episode of The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon. That Christmas, Apple featured a Voice-O-Graph record in a holiday commercial. And this year, people on the East coast got at least two chances to see one of the machines in person, when Brooklyn’s Rough Trade record store temporarily parked one on-site, and D.C.’s Songbyrd Record Cafe announced it had acquired one of its own.

Like vinyl records, old-fashioned recording booths are piquing the interest of young folks drawn to the quaint and pre-digital. And Bill Bollman deserves much of the credit.

A 55-year-old patent attorney in Bethesda, Maryland, Bollman has single handedly revived the market for Voice-O-Graph recording booths.

“These things — they haven’t been in the public eye for 60, 70 years,” says Bollman, speaking from his office in downtown D.C. “Now there’s a spike.”

A spike indeed. The White Stripes’ Jack White — who purchased a Voice-O-Graph through Bollman and brought it onto The Tonight Show — says his booth has recorded more than 1,000 musicians since he unveiled it at his label’s Nashville headquarters two years ago. That group includes Neil Young, who cut his 2013 record A Letter Home with the machine.

“You get inside it and you’re just in the zone,” Young said, showing off the Voice-O-Graph on Fallon’s show. “You close the door, and it’s like you’ve gone back. Way back.”

History inside the booths

When Songbyrd Record Cafe opened in Northwest D.C. last spring, its owners boasted that they’d acquired an authentic, 1940s recording booth for the shop. For just $15, they said, customers could make their own record at the café. It sounded like a hipster gimmick. But Songbyrd’s record machine is about as real as it gets.

Songbyrd’s Voice-O-Graph is a Bollman job. Purchased in the mid-2000s, it was the second booth he ever restored.

“I bought that booth from a guy out in California,” Bollman says. “It came to me in pieces. Literally.”

“J.D. + B.G.” (via Bill Bollman)

The man who sold the machine to Bollman said it had spent time inside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood in the ‘50s. That seemed likely, Bollman says, particularly when he noticed an etching inside the box: HO 48111, the theater’s old phone number. And when Bollman looked closer, he found two other etchings: one said “James Dean ‘55.” Another spelled out “J.D. + B.G.,” surrounded by a little heart.

Bollman contacted Lew Bracker, who wrote a memoir about his friendship with James Dean called Jimmy & Me. Bracker told Bollman that before the actor died in 1955 at age 24, he made the rounds at Hollywood movie theaters. One of them could have been Grauman’s. Then Bollman examined Dean’s old letters and found the initials “B.G.,” written in a similar way. Those initials belonged to a woman Dean dated for two tempestuous years: Barbara Glenn.

Bollman says he’s nearly sure that James Dean made his mark on the 1947 Voice-O-Graph booth. He just can’t prove it.

Later in its life, the machine turned up in Santa Monica. It appears in the 1965 movie Inside Daisy Clover, one of Robert Redford’s earliest films. In the opening credits, star Natalie Wood records herself singing inside a booth on the Santa Monica Pier. The outside of the booth advertises a price: your voice on a record for just 25 cents.

(The price was artificially low, Bollman discovered. Inside Daisy Clover was set in the 1930s. To coincide with the era, someone had replaced 35 cents with 25. But they overlooked the fact that the booth didn’t exist in the ’30s.)

Today, that same recording booth — once used as a Hollywood prop and possibly vandalized by James Dean — sits in a Northwest D.C. cafe, mostly unused.

Songbyrd co-owner Alisha Edmonson says her business’ Voice-O-Graph needs a new part. It’s currently out of commission, and it’s been that way for months.

An audio time capsule

In 2008, Bethesda Magazine ran a story about Bollman and his wife, Barbara — or rather, about their basement.

“Clearly, this is not just any basement,” wrote author Julie Beaman. In addition to a basketball court and a climbing wall, she reported, the space housed a 1956 soda machine, a 1951 phone booth, a 1948 popcorn maker and 15 vintage arcade games, all of which Bollman had restored, either by himself or with help.

Bollman is a fanatic for coin-operated machines. He’s collected and refurbished them for years, funding his hobby with his career as a patent attorney. Voice-O-Graphs are one of his more recent obsessions. He got into them about 15 years ago.

“They talk about [the Voice-O-Graph] as being the first text message,” Bollman says. Then he adds — modestly — “I wrote the patent of text messaging, by the way.” (He’s not lying.)

Like early text messages, original Voice-O-Graph transmissions could only be so long — 65 seconds. Bollman has collected hundreds of those recordings, each one a sliver of history.

“Thanks for all the papers I got the other day, mother,” says a woman on an early recording. “Boy, I sat down and read for nearly an hour, and the washing never did get finished that day.”

“Happy New Year,” a man says to a friend, “and don’t forget to get drunk.”

Some people sing, some read prepared letters, others recite poetry. Bollman picked some of his favorite Voice-O-Graph recordings and strung them together into a 50-minute audio time capsule.

Bollman’s Voice-O-Graphs come from everywhere. He got one from a guy in New Jersey who said he plucked it off a truck headed to a scrapyard in the ‘80s. It sat in his mother’s garage for 28 years.

Then there’s the booth he bought from a Texas woman whose brother-in-law had kept it on his porch for a few decades. “Fortunately, Texas is dry and hot,” Bollman says. He refurbished the old machine and sold it to a scotch whisky distillery, Aberlour. The company now has the Voice-O-Graph on a world tour. As of this writing, it’s sitting inside London shop Phonica Records; next it goes to Canada.

Bollman says his first Voice-O-Graph restoration took eight years. He often sells the units he overhauls — he declines to say for how much — but he insists he doesn’t do it for money alone.

“All coin-op hobbies, we call it a labor of love,” Bollman says. “It’s not really a profit-driven thing.”

The Voice-O-Graph micro-industry is greased by wealthy collectors like Jack White, who first connected with Bollman in 2011. Bollman says White was hunting for a bag of wax — the kind used in another old coin-operated machine, a Mold-A-Rama. (Bollman knows a lot about them, too; he runs the website moldville.com.) Bollman’s pal in Florida usually supplied White with wax, but he’d left town. So the attorney offered to hook White up.

“I said, ‘I’ll send Jack a bag of wax,’” Bollman says. When he popped it in the mail, he slipped in an old Voice-O-Graph disc with a note. It said, “You guys have to get one of these booths. It’s right down your alley.”

White’s record label called Bollman right away, he says. They told him the rock star had been looking for a Voice-O-Graph for 10 years. It just so happened Bollman knew where to find one.

After White bought his first Voice-O-Graph through Bollman — he says the musician has acquired at least two — he opened it up to the public at his Third Man Records storefront in Nashville. Anyone can make a record in the booth for $15. Some convert their recordings to mp3 and get them posted on the label’s website. (A Third Man Records staffer said Jack White was unavailable to comment.)

Third Man Records’ Voice-O-Graph has proved to be enormously popular, says Angelina Castillo, the storefront’s manager. Though, it requires a lot of TLC.

“It’s very, very difficult” to maintain, Castillo says, and parts occasionally stop working. But the store tries to manage customers’ expectations, reminding them that the Voice-O-Graph is ancient by today’s standards.

“They are usually quite understanding after they see [the machine],” Castillo says. “They say, ‘Oh, wow, this thing is truly wacky.’”

White’s label markets its Voice-O-Graph as a novelty. But Bollman sees the devices as something more.

“It’s hard to appreciate the function they served in society back when they were introduced,” Bollman says. “They served a function — to be able to speak with someone away at war.”

Every so often Bollman will come across a recording that makes him feel like he’s doing more than collecting old things. Not long ago, he says, he found a Voice-O-Graph platter posted from Pearl Harbor the year after Japanese forces attacked the base in 1941. Bollman examined the address on the sleeve, and mailed it to a California woman with the same last name. He thought she might be related to the soldier who made it.

Bollman could have fished out the record and tossed it on his turntable like he’s done on countless occasions. But this time, it didn’t seem right.

“I didn’t feel like I should be the one to open it,” he says.

Bill Bollman appears on WAMU’s Kojo Nnamdi Show Thursday, Oct. 29. Stephen Kearse contributed to this report.

Pingback: Arts Roundup: New York, New York Edition | Washington Metro Bugle()

Pingback: Arts Roundup: New York, New York Edition | Washington Metro Bugle()