For a couple of years in the late ’80s, Soulside (or Soul Side) was as prominent and as influential as any band in Washington, D.C.’s Dischord Records scene. The first waves of D.C. punk and hardcore had subsided, Fugazi’s 1990s heyday was still ahead, and four guys from Wilson High School put out the Trigger EP, encapsulating a moment when the American underground was figuring out where to go next.

Next Sept. 16, Dischord issues a remastered version of that eight-song 1988 release on vinyl and digital formats, with a tracklist that also includes Soulside’s 1989 single, “Bass/103.” The songs—expertly punched-up and rounded-out by engineer TJ Lipple—point confidently toward the next decade, when Dischord would be known more for wildly creative post-punk than for full-on fury. The title track alone—with its rolling bassline, guitar squawks and emotional buildups—foretells a lot about ’90s rock.

Soulside called it quits in 1989, with vocalist Bobby Sullivan moving on to more reggae-influenced and funk-flavored sounds, including Seven League Boots, Rain Like the Sound of Trains and Sevens. Lately he’s leaned acoustic with a sporadic project called Spontaneous Earth and experimented with beat-driven message songs under the moniker Moving Temple. The other three Soulside members—guitarist Scott McCloud, bassist Johnny Temple and drummer Alexis Fleisig—went on to fill out the lineup of Girls Against Boys with Eli Janney.

Sullivan left D.C. soon afterward, settling in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1997. An advocate of veganism and raw food—particularly since his 1989 diagnosis of early-stage lymphoma, a condition he says he manages with diet—he’s now a proponent of food co-ops and a manager of one, and also a social-justice advocate with connections to activists such as MOVE‘s Ramona Africa. He spoke with Bandwidth about the Trigger era, what kind of man he is now, and how it all ties together. He says he still has positive relationships with the other members of Soulside, and that they’ve been in touch because they’re considering doing some shows. But he wouldn’t elaborate on that.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Bandwidth: So let’s get the obvious question out of the way first. How did the reissue come together?

Bandwidth: So let’s get the obvious question out of the way first. How did the reissue come together?

Bobby Sullivan: It was something Dischord initiated. And we were certainly all about it. … The richness of vinyl, you just can’t compare it. And I’m so glad that vinyl has remained a viable medium for music. … We were really excited that they were doing it, and then hearing how it was remastered, it sounds so much better than the original. … It is so great listening to it. We sound more powerful than ever.

You’ve had a lot of time, and distance, and a lot of other bands between now and then. Talk about the journey you’ve been on since this music first came out, or talk about how much you’ve changed since then.

Truth be told, I have four kids, and I’ve rarely listened to hardcore music anymore. And there was a period of 15 to 20 years where I didn’t listen to Soulside. But then when I went back—I can’t remember if I just found an old CD or what—but I listened to it, and what struck me so significantly was, I haven’t changed a bit! [laughs] Those lyrics were written by a 17-to-21-year-old, but I haven’t changed at all. It was really striking to hear that.

“We were part of the movement to end slam dancing… it completely excludes most women.”

When you say you haven’t changed, do you mean you haven’t changed your outlook? Or the things that made you angry still make you angry in the same way?

I’m still writing songs about the same stuff. Or different stuff but the same ethics. We had a lot more idealism then, and different things were important to us. You know, I might not write a song now about a cigarette in your hand being a big issue. More like Somalia, what’s going on there. My approach to music is very much how it was then—I personally wanted to change the world, and it was an idealistic approach for sure, but to me, what’s so interesting about music is that it really can change things. And I always felt that there was a real responsibility—for people who get up onstage and project ideas—to do the right thing.

Especially for that album, we were really conscious of the fact that we were in a scene that had already done something really special. And that “hardcore” had been defined, and it had originated among many of the people that we were around and learning from. There was a great sense of mentorship from the older brothers in the scene. People like H.R. [of Bad Brains], my own brother [Mark Sullivan, of pre-Dischord band the Slinkees and later Sevens and Kingface], Ian [MacKaye], Henry [Rollins], everybody was very encouraging. And we definitely felt a responsibility to carry on that tradition, and not just be foolhardy about what we were doing. And it wasn’t a party—we were coming from something that was really significant, and I think everybody felt like, “OK, there is gonna be a next thing.” And Nirvana ended up happening to break through. Everybody at that time knew something was gonna happen. Nobody knew what.

I looked back at an interview with you in a British fanzine from that era, and you were already talking about being more into funk and hip-hop than hardcore.

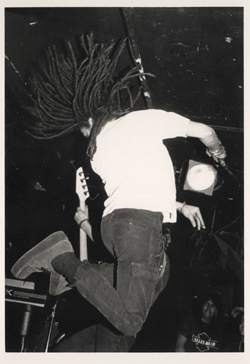

We were also part of the movement to end slam dancing. It’s such a great thing to have happen when there’s 20 people in the room. And there were definitely some shows … where’s it’s this incredibly supportive, friendly thing. You’re jumping off the stage and people are catching you and no one’s getting hurt, but when it’s a packed crowd—man! And it completely excludes most women.

That was definitely part of our sound. We wanted people to really dance. You know, we were from D.C. We were going to dance parties starting in like 4th grade. The idea of the slam-dance thing was a little alien—it was fun, but it’s more like guys roughhousing … Part of it was, it’s not just about the band, it’s what’s going on in the audience, too, and I think that’s where slam-dancing was really cool—everybody in the room, participating. But, y’know, come on … shake your booty a little bit more.

“Us and Fugazi used to practice catty-corner from one another in the neighborhood where our parents lived. And we’d be taunting them, like, ‘Yo, we just came up with three new songs!'”

Something that speaks to all of this: You’ve taken on B. Subtle as a stage name now. How does this all feed into that? It seems intentional to me, relative to what you’ve said already. Talk about who B. Subtle is.

I was involved in this Rastafarian prison ministry. We volunteer at prisons in North Carolina and South Carolina to do religious services for Rasta inmates, and the elder who heads that up, he gave me that name. It was funny, because he was like, “Oh man, you’re gonna love this one: B. Subtle.” He was like, “Because you’re so [freaking] subtle. You have an agenda that you’re pursuing, you are trying to get something done, but you’re really subtle about it.” So that’s who that is.

Are you a practicing Rasta, then?

It’s interesting, because when it comes to the prison administration, it’s definitely a religion. I don’t view it as that. It was something that H.R. introduced me to when I was really young. And me and Johnny Temple, the bass player, we worked at a reggae record label all during Soulside. It’s something that—especially growing up in D.C., you definitely find yourself reasoning with Rastas. So for me, I’m definitely more into the movement of Rastafari, not so much the religion, because in my view it’s not something that’s supposed to set you apart from everyone else—it’s something that is an incredible unifying force. I think the Internet has really destroyed the message of Rastafari in a lot of ways, because what you see more is the “fire burn” element. It’s almost like, the most extreme voices are the loudest, right? When people think of Islam, they think of the Taliban, when they think of Christianity now, it’s the tea party, and the same thing is going on with Rasta, where it’s not as inclusive as it felt to me when I was younger. So yes—I definitely have to cite my influences, and I think that’s important.

It’s interesting, because when it comes to the prison administration, it’s definitely a religion. I don’t view it as that. It was something that H.R. introduced me to when I was really young. And me and Johnny Temple, the bass player, we worked at a reggae record label all during Soulside. It’s something that—especially growing up in D.C., you definitely find yourself reasoning with Rastas. So for me, I’m definitely more into the movement of Rastafari, not so much the religion, because in my view it’s not something that’s supposed to set you apart from everyone else—it’s something that is an incredible unifying force. I think the Internet has really destroyed the message of Rastafari in a lot of ways, because what you see more is the “fire burn” element. It’s almost like, the most extreme voices are the loudest, right? When people think of Islam, they think of the Taliban, when they think of Christianity now, it’s the tea party, and the same thing is going on with Rasta, where it’s not as inclusive as it felt to me when I was younger. So yes—I definitely have to cite my influences, and I think that’s important.

Ramona Africa herself was a tremendous influence on me. I spent a bunch of time with her. Just hanging out with her in Philly and setting up speaking engagements for her in the D.C. area. And MOVE, in fact, really opened up the idea to me of having kids, because I learned through them that you don’t have to change once you have kids. Actually, it’s healthier to be more who you are, so they can see that. MOVE was as much an influence on me as Rasta, and I always felt that the mistake people who are into Rastafari make is emulating Jamaican people. I think that’s a real mistake. Certainly to appreciate Jamaican culture, but if we are going to adopt a culture of livity like that, it only makes sense to do it our way, in our cultural context, just the way MOVE did.

The last Soulside tour was six months long. We were on the road for six months. It was two months in the U.S. and four months in Europe. This was the “Trigger” tour, and the timing was just right, and we were the first American band to play in East Berlin, the wall was still up. And we played three cities in Poland where we were the first U.S. band … we went all the way from Norway to Greece, and after I got home, I got diagnosed with early stages of lymphoma cancer [caused by Epstein-Barr virus]. So that’s where the awakening started happening for me, with food. That’s where MOVE’s living-food thing was a real influence.

“That’s what I think is interesting today, that people don’t see the linkage between reggae and punk. The way it was so obvious back in the day with The Clash and The Ruts, and even Bob Marley’s song, ‘Punky Reggae Party.’ To me, I’m living the punky reggae party, and not everybody gets it.”

Where are you at now, musically?

It’s the exchange of ideas that I love. I do harken back to those days where we had a scene, where it was so mutually beneficial how all the bands worked together. We shared equipment, fliered for each other. Us and Fugazi used to practice catty-corner from one another in the neighborhood where our parents lived. And we’d be taunting them, like, “Yo, we just came up with three new songs!” And so I do miss being part of a scene. And I’ve never pictured myself as a solo artist. I like being part of a band, a collective where everybody’s putting in the same amount. But that’s been hard for me to do. But I never stopped writing.

So my thing is, I’m just waiting for an opportunity, because I have so many songs … and I actually would like to do some harder music, because it’s been awhile. I did a reunion with Seven League Boots … I think some of my favorite harder music would be like Pailhead or Egghunt, that stuff Ian did [where there was a bit of an electronic element]. So I could see doing something like that. But I really mostly like playing acoustic at this point. But now it’s the second generation. So my kids, like my 15-year-old, she wore a Soulside shirt to school today, she was really excited. And they’re making music, and so that’s my goal at this point—to make music with them, and just have a fun family band to fool around with.

So my thing is, I’m just waiting for an opportunity, because I have so many songs … and I actually would like to do some harder music, because it’s been awhile. I did a reunion with Seven League Boots … I think some of my favorite harder music would be like Pailhead or Egghunt, that stuff Ian did [where there was a bit of an electronic element]. So I could see doing something like that. But I really mostly like playing acoustic at this point. But now it’s the second generation. So my kids, like my 15-year-old, she wore a Soulside shirt to school today, she was really excited. And they’re making music, and so that’s my goal at this point—to make music with them, and just have a fun family band to fool around with.

What about Spontaneous Earth?

It’s basically my classical acoustic guitar approach to reggae [chuckles]. As a musician, the reggae skank just comes really natural to me on the guitar, but I view it more as like, my ideal band would be a combination of Sly and the Family Stone and the early Wailers. … [As far as reggae goes], the DIY style of it all is very relevant to the punk scene. That’s what I think is interesting today, that people don’t see the linkage between reggae and punk. The way it was so obvious back in the day with The Clash and The Ruts, and even Bob Marley’s song, “Punky Reggae Party.” To me, I’m living the punky reggae party, and not everybody gets it [laughs].

Any other thoughts that you want to leave us with?

I’m just happy that Soulside was one of those bands that never made it into the mainstream music industry. I think that’s the greatest thing about looking back at it. We didn’t make that step of signing to a major label and riding the wave of grunge. I think we were really lucky in that we got to ride the wave of wider acceptance for hard music, but we didn’t get to the point where it became a moneymaking venture. So it remained something that was really pure, and exactly what we wanted it to be. Never did we write a song saying, “This song’s gonna sell more,” or “This is what people are gonna like.” We did exactly what we felt like doing.

Photo credits, from top to bottom: Shawn Scallen, Brian Simmons, Dischord Records, Shawn Scallen