After investing thousands of dollars and working long hours to produce a new record for noise-punk band Roomrunner, the day had finally come for Fan Death Records co-owner Sean Gray to celebrate with the band at a show in Baltimore. But instead of enjoying the night with the band and its fans, Gray found himself spending a few hours alone on the sidewalk.

For Gray, who has cerebral palsy and uses a walker, it was yet another show he missed because a venue was inaccessible.

“The steps were so wide and so rickety and the ceiling was so low and steep, that my friend couldn’t even help me down the stairs,” he says.

Stairs, narrow doorways, cramped corridors: They’re barriers to mobility-impaired people in any building, but they pose a particularly large problem in the underground music scene—even in D.C., a government hub that’s otherwise pretty accessible.

Stairs, narrow doorways, cramped corridors: They’re barriers to mobility-impaired people in any building, but they pose a particularly large problem in the underground music scene—even in D.C., a government hub that’s otherwise pretty accessible.

Bands all over the country get their start playing unconventional spaces like houses and dive bars—and for a few reasons, those spaces aren’t always subject to the regulations established by the Americans With Disabilities Act, the pivotal civil rights legislation that celebrated its 24th anniversary last month.

Consequently, even while D.C.’s DIY scene experiences a small-scale renaissance, a segment of the music community is effectively barred from participating—often by factors as common as a flight of stairs.

But with such glaring obstacles preventing mobility-impaired people from going to shows, activity around the issue seems minimal in D.C.’s music scene. Why don’t more people talk about accessibility? And how can venues and show-bookers do better by disabled music fans?

Understanding Accessibility

The good news is that many of D.C.’s big commercial venues comply with ADA, which affords basic rights to people with physical or mental impairments and establishes accessibility requirements for new buildings. It also makes sure that buildings that predate the legislation meet certain accessibility standards when possible.

The bad news is that many other D.C. venues don’t comply with ADA’s standards—and they don’t always have to.

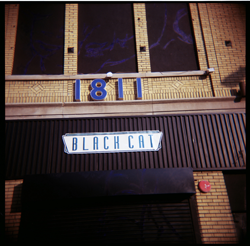

If you use a mobility aid like a wheelchair or walker, you’ll do fine at numerous D.C. spots including the Howard Theatre, The Hamilton, Sixth & I Historic Synagogue, U Street Music Hall and Gypsy Sally’s. They make it easy with elevators that open their levels to all patrons. Black Cat gets high marks not only for its wide front doors and accessible backstage concert space, but also for the freight elevator to its main concert room upstairs.

Some DIY spots do accessibility well, too: Columbia Heights church St. Stephen’s is equipped with ramps, and Comet Ping Pong and Takoma Park’s Electric Maid are easy to enter.

Some DIY spots do accessibility well, too: Columbia Heights church St. Stephen’s is equipped with ramps, and Comet Ping Pong and Takoma Park’s Electric Maid are easy to enter.

Some major music venues in town are only partially accessible. Disabled patrons can easily navigate the 9:30 Club—unless they want to visit the balcony, which requires a hike up a set of stairs. Everyone can access Rock & Roll Hotel‘s first floor, too, but not the second-floor dance hall or rooftop bar.

The concert rooms at DC9 and Velvet Lounge can only be accessed via a flight of stairs, making shows at those venues inaccessible to customers who use mobility aids. (Though DC9 booker Steve Lambert says club staff is happy to help showgoers up the stairs.) Critically, plenty of house venues are inaccessible, too—they’re often old rowhouses with staircases to the front door and stairs to the basement. Unfortunately, places like these are not required to go accessible, assuming they meet certain criteria established by ADA legislation.

Marian Vessels, director of the Mid-Atlantic ADA Center, says that since so many D.C. buildings were built before the ADA’s construction requirements took effect in 1992, they were built without accessibility in mind. But she says if an accommodation is cheap and easy, businesses must make it. That means if the only thing preventing your venue from compliance is, say, an easily widened doorway, you must modify it. But for many businesses, constructing a ramp or adding an elevator would be either physically or financially impracticable.

If it’s structurally and financially feasible for a house venue to be made accessible, the property owner has to do it—because when that house hosts shows, it’s considered a public gathering place.

Private residences normally don’t have to comply with the ADA. But the rules change for houses that host public events. If it’s structurally and financially feasible for a house venue to be made accessible, the property owner has to do it—because when that house hosts shows, it’s considered a public gathering place.

“If you put flyers out that say something like, ‘Free movie night! Come as you are! We’ll have a good time!’ now you’ve become a place of public accommodation,” says Jim Pecht, an accessibility specialist at the United States Access Board.

Erik Butler, who runs D.C. house venue The Rough House, says that his space has a makeshift ramp. If other houses did the same, they could open doors they might not have realized were closed.

Going accessible offers a longer-term gain, too. Residences serve as seedbeds for the local music scene, particularly in D.C., where house shows have been happening for decades (and not just in the punk community). If a disabled music fan can’t get into a basement show, it means one less person is supporting local music—and that’s no good for a DIY scene like D.C.’s, which normally prides itself on its inclusiveness.

“Just Treat Everyone Like A Person”

You couldn’t accuse D.C.’s punk scene of broad insensitivity; it’s a community that tends to be clued into social-justice issues, and promoters, venues and musicians regularly support progressive or otherwise worthy causes.

Take D.C. punk activist group Positive Force, which has hosted numerous benefit concerts over its nearly 30 years of existence, and the national happening Punk Rock Karaoke, whose local iterations have benefited an assortment of D.C.-area organizations like Girls Rock! D.C., D.C. Books to Prisons and Helping Individual Prostitutes Survive.

Yet for all its idealism, D.C.’s DIY music scene doesn’t seem as attuned to accessibility as a social-justice issue. Evidence exists in the number of shows hosted at inaccessible venues, particularly houses.

Then again, it’s difficult to gauge the size of the accessibility issue in the D.C. music scene, because it’s tough to count the number of disabled people who aren’t coming to shows. But ask people who work at venues, and they’ll tell you they hear from people about accessibility on a fairly regular basis.

Then again, it’s difficult to gauge the size of the accessibility issue in the D.C. music scene, because it’s tough to count the number of disabled people who aren’t coming to shows. But ask people who work at venues, and they’ll tell you they hear from people about accessibility on a fairly regular basis.

Black Cat booker Candice Jones says the 14th Street NW club gets phone calls about accessibility up to several times a month, and Rock & Roll Hotel Marketing Manager Molly Majorack says the venue fields calls about it once every two months. (Majorack also says security staff at the H Street NE club take a course and receive a certificate through the city to train on hospitality for people with disabilities.)

Natalie Illum (shown above), a disability activist, performer and poet, says that she moved to D.C. in 1999 specifically because of its accessibility to people like herself, who identify as having a physical disability. “It’s by default one of the most [ADA] compliant cities in the United States,” she says. “It’s why I live here.”

But Illum became frustrated by local spaces and stages that didn’t accommodate performers with disabilities. “Stages are not necessarily built with people who have mobility issues in mind,” she says. Her idea for a barrier-free performance series inspired a campaign that aimed to raise funds for a venue, ASL services, an accessibility ramp and other costs. She hasn’t met her goal yet, but the campaign is ongoing.

“Eight or nine times out of 10, there’s some drunk guy at the end of the show who tries to clear a path for me, showing the world, ‘We got a disabled guy coming through! Move out of the way!’ and then there’s this spotlight put on me. Is that person trying to help me or are they trying to make himself feel better?” —Sean Gray

Sight-impaired scenester and photographer Ahmad Zaghal goes to a lot of shows—by his count, four or five per week—and he says that for the most part, venue staff is great about helping him out. But he adds that accessibility doesn’t usually occur to able-bodied people until they are confronted with it. “It’s mostly an awareness issue,” he says. “It doesn’t really register until you’ve encountered it in some way.”

Because Zaghal turns up at so many local concerts, he says, many of his fellow showgoers are already aware of his disability, so he doesn’t endure a lot of blatant ignorance or harassment. But Sean Gray—who co-hosts a WMUC radio show with Zaghal—says he’s been confronted with a certain kind of unpleasant helpfulness.

“Eight or nine times out of 10, there’s some drunk guy at the end of the show who tries to clear a path for me, showing the world, ‘We got a disabled guy coming through! Move out of the way!’ and then there’s this spotlight put on me,” Gray says. “Is that person trying to help me or are they trying to make himself feel better?”

Gray compares that scenario to one that has dogged women at shows for years. “It’s the same thing if you said, ‘There’s a woman at this hardcore show, so we better make sure nobody [messes] with her.’ Putting that spotlight on you highlights that you’re The Other and you’re the oppressed group.”

Memphis-based guitarist Will McElroy, who has cerebral palsy, has toured with indie bands Magic Kids and Toxie (shown below). He reports few problems with the venues he’s played over the years. But still, he says, “More awareness could never hurt.”

McElroy says interactions between disabled and able-bodied showgoers should follow a simple but powerful rule: “Just treat everyone like a person.”

What Can Be Done?

Venues don’t have the option of a silver-bullet solution to their accessibility problems because disabilities exist on a spectrum. In other words, a ramp isn’t especially helpful for someone who is hearing-impaired, and ASL translation is useless for a someone who needs to circumvent a flight of stairs.

“There isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer,” Gray says. “It would be ignorant of us to say ‘This is what the venue or the staff or the public needs to do to make things better.'”

“There isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer,” Gray says. “It would be ignorant of us to say ‘This is what the venue or the staff or the public needs to do to make things better.'”

But all venues can take steps to do better by disabled showgoers. Independent promoter Sasha Lord, who books Comet Ping Pong, says getting the word out about local venues’ accessibility—or inaccessibility—is key. “Be proactive,” she says. “Every venue should assess their accessibility. Knowing your limitations should be the first thing.”

Venues could also include accessibility information on their websites, social-media accounts and flyers. Numerous local venues’ websites tell people to call with questions about ADA compliance. But why should anyone have to make a phone call?

“If I have that information in front of me, it will make the whole interaction, going to that venue, a whole lot easier,” says Gray. “Be public about what is accessible or not.”

Marian Vessels says that to eliminate barriers, venues of all kinds need to think creatively. She suggests that show spaces install inexpensive portable ramps where they can, and those that cannot could consider installing speakers or monitors to broadcast the performance into an accessible space in the venue or offsite. “It’s not ideal,” she says, noting the social aspect of live music. But it’s better.

“If the artist says, ‘I won’t play a venue that’s inaccessible or isn’t a safe space,’ then it puts the venue’s back against the wall. … No band is too small to put their foot down.” —Sean Gray

Independent promoters can opt to host shows in more accessible venues, too. Instead of booking bands at houses with no viable entry for disabled people, look elsewhere.

Gray suggests that performers take up the torch, too, in order to raise the issue with venues. “If the artist says, ‘I won’t play a venue that’s inaccessible or isn’t a safe space,’ then it puts the venue’s back against the wall,” he says. “If enough artists do that, a venue will lose money and start to pay attention. No band is too small to put their foot down.”

Vessels agrees. If a space is inaccessible, “tell the venue why you’re not going in,” she says. That way, venue owners may see how becoming more ADA-compliant could benefit not just people’s lives and the scene, but—in the case of commercial venues—their bottom line. If spaces are still not barrier-free when they could be, maybe they’re just unaware of the problem.

“We don’t expect them to know the answers,” Vessels says. “But they have to know enough to ask.”

The Mid-Atlantic ADA Center’s website provides an easy-to-use guide to tax credits and deductions that are available for businesses to make their space more accessible. Also, the annual Leadership Exchange in Arts and Disability Conference provides valuable information about accessibility in the arts.

Photos, from top: Images by Flickr user Marlon Dias, Stewart Chambers and Alex Barth used under a Creative Commons license; images of Toxie and Natalie Illum courtesy of the artists.

Correction: The original version of this blog post said buildings that predate ADA legislation are “grandfathered out” of its regulations. No older buildings are grandfathered out—all must comply to the extent they can be made accessible—but they were less likely to be built with accessibility in mind. The post has been corrected.

Pingback: WAMU 88.5’s Bandwidth: Is DC’s Music Scene Shutting Out Disabled Music Fans? | The Glove Compartment()

Pingback: Arts Roundup: Corcoran Split Edition - Arts Desk()

Pingback: Is D.C.’s Music Scene Shutting Out Disabl...()

Pingback: District Line Daily: Hold That Gun Law - City Desk()

Pingback: “Is This Venue Accessible?” New Website Tells D.C. Showgoers the Answer - Arts Desk()