When Punk the Capital filmmaker James Schneider approached D.C. Public Library about starting a punk-rock archive, he discovered that the library was already a step ahead of him.

The idea had been kicking around for a few years, says Michele Casto, a special collections librarian in DCPL’s Washingtoniana collection. Casto says she’d started looking into it some time ago, but she later changed jobs and the idea fell through the cracks. It wasn’t until after she’d transferred back to Washingtoniana—and Schneider got in touch—that the plan sprouted legs.

Now the D.C. Punk Archive is officially coming together at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, in the hopes that its physical and digital components will help capture what Casto calls a “big piece of D.C. history.”

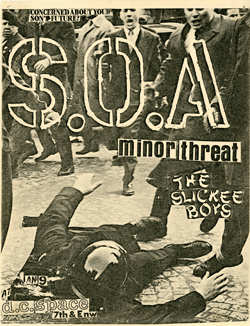

The punk archive aims to date back to 1976—the year the Slickee Boys released their Hot and Cool EP, a recording now seen as a key predecessor to D.C. punk and hardcore—and track the scene to its bustling present day. A $20,000 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services will pay for an online multimedia showcase so both locals and out-of-towners can explore the collection. The library hopes to unveil the web portal in the spring or summer of 2015.

The punk archive aims to date back to 1976—the year the Slickee Boys released their Hot and Cool EP, a recording now seen as a key predecessor to D.C. punk and hardcore—and track the scene to its bustling present day. A $20,000 grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services will pay for an online multimedia showcase so both locals and out-of-towners can explore the collection. The library hopes to unveil the web portal in the spring or summer of 2015.

When Schneider contacted DCPL, Casto says, he said he’d come across various punk collections in people’s houses while making his in-progress documentary with Paul Bishow, and some of those pieces of the past could be in danger of being lost. It seemed like a smart idea to house vulnerable objects like flyers, records and photographs in a venue that was both secure and accessible to the public. Casto, of course, agreed. “That’s the gospel of preservation: making sure these things don’t disappear,” she says.

But what would a D.C. punk archive look like, and whose stories would it tell? DCPL reached out to people in Schneider’s network to solicit guidance for the project. Their efforts led to one well-attended meeting last year, where numerous figures in the punk scene showed up to offer their feedback.

Cynthia Connolly, the photographer who assembled the seminal punk-rock photography book Banned In D.C. and formerly worked at Dischord, attended the meeting. She says she stressed the importance of bringing in original, handmade material with distinctive and personal touches like pinholes and tape marks. “Any subculture thrives on the passion of the people who are involved,” Connolly says, “and those little details are important.”

Now the library is asking the public to donate their own pieces of D.C.’s punk history to the library. It already has some items, including a flyer collection (now being digitized) donated by musician Eddie Janney. But right now the library has mostly secured “firm verbal commitments” from several people with small collections of things like records, film footage and posters. Some folks with larger collections have expressed their support, but Casto says they’re “waiting to see where it goes before deciding what they want to do.”

As items come in, Casto says the library is harnessing people power to organize it all. It’s already recruited dozens of volunteers that it will train as “community archivists” to help catalog and digitize donated artifacts, and it’s working with the people behind the University of Maryland’s fanzine collection to see how they can pool their resources.

The library hopes to use this process as a template for another music project it wants to pursue: a D.C. go-go archive. That initiative is on hold at the moment; a previous attempt to solicit donations from the go-go community hit a wall, Casto says. They’re hoping to reboot it after learning some lessons from the punk collection.

Schneider says that now seems like an opportune time to build an archive like this. For one, D.C.’s punk scene is surprisingly energetic right now, with new bands and venues cropping up regularly. Plus, he and Bishow are readying Punk the Capital for a release in late 2014 or early 2015, and Scott Crawford’s Salad Days film is also in the works.

But even as the local punk scene grows, D.C. is speedily transforming into a wealthy, built-up city with fewer obvious traces of its musical heritage. The filmmaker says it should be a priority to preserve and reflect on what came before.

“With the city changing so fast, on so many fronts,” Schneider says, “it’s more important than ever now to ensure that the city’s identity is firmly anchored before a remodeled city takes over.”

D.C. Public Library is currently accepting items for the D.C. Punk Archive. Contact Michele Casto or Bobbie Dougherty for more information. The library has also set up a Google Form for members of the public who want to suggest D.C. music for the archive. Follow @dcpunkarchive on Twitter.

Both images: Materials donated by Eddie Janney

Pingback: 15 Incredibly Specific Special Collections Libraries()